HDC will work with the Addisleigh Park Civic Organization to provide resources to adjust their zoning in order to protect the historic character of their neighborhood, as well as promoting the neighborhood as a cultural and historic destination.

HDC will work with the Addisleigh Park Civic Organization to provide resources to adjust their zoning in order to protect the historic character of their neighborhood, as well as promoting the neighborhood as a cultural and historic destination.

Belmont was originally part of the Town of West Farms (incorporated 1846), which, with the Towns of Kingsbridge and Morrisania, was annexed by New York City in 1874. From 1901 to 1973 Belmont was served by the Third Avenue Elevated, which had stops at 180th Street, 183rd Street and Fordham Road.

Today, the easiest way to get to Belmont from Manhattan is by Metro-North to Fordham. A short walk east along Fordham Road, with Fordham University’s beautiful campus on one’s left, takes one to Arthur Avenue, the main commercial artery of Belmont, renowned as The Bronx’s “Little Italy,” though the neighborhood also contains sizable representations of Albanians and Mexicans. Notable residents have included the esteemed novelist Don DeLillo (b. 1936), who was born and grew up near Arthur Avenue (and who attended Fordham University) and was the recipient of the National Book Award in 1985 for his novel White Noise. DeLillo’s novel Underworld (1997) is partly set in the neighborhood.

Perhaps the most famous of Belmont’s native sons is Dion Francis DiMucci (b. 1939), who grew up at 749 East 183rd Street, at Prospect Avenue. A member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Dion (he has always been known by the single name) was one of the most popular recording artists in the world in the late 1950s and 1960s, and has been counted a principal influence by Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen and Lou Reed. Dion got his musical start by singing a cappella on Belmont street corners. With three other neighborhood boys, he formed Dion and the Belmonts in 1957. Belmont is also notable as the setting of the Academy Award-winning film Marty (1955). Locals like to point out that actor Joe Pesci was “discovered” by Robert DeNiro while tending bar at Amici’s, an Arthur Avenue restaurant. Another important cultural touchstone for the neighborhood is the off-Broadway play, film, and Broadway musical A Bronx Tale by Chazz Palminteri.

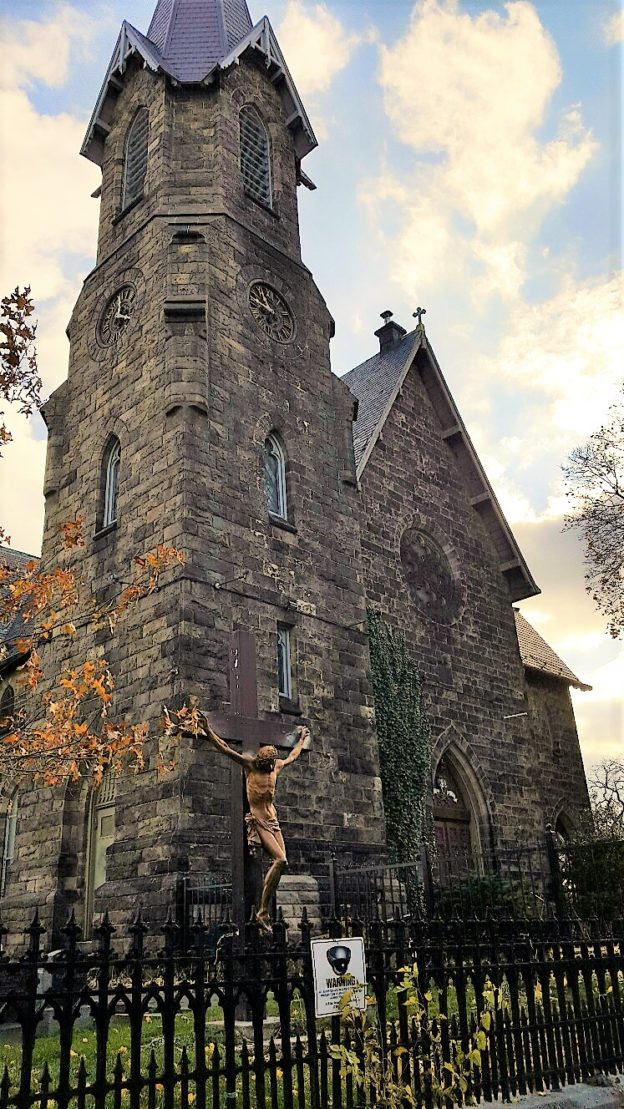

Fordham University, on the northern border of Belmont, originated as St. John’s College in 1841. The campus was built on the Rose Hill manor farm of Robert Watts. Renamed as Fordham University in 1907, it was the first Roman Catholic college in the northeastern United States. Among Fordham’s countless notable alumni are Congress Member Geraldine Ferraro, Governor Andrew Cuomo, CIA director William Casey, Attorney General John Mitchell, football coach Vince Lombardi, baseball announcer Vin Scully, novelist Don DeLillo, and actor Denzel Washington.

Belmont was once part of the landholdings of the Lorillard family. The Lorillard tobacco firm was founded in 1760 and moved to this part of The Bronx in 1792. In 1870, the family moved their manufacturing operations from The Bronx to Jersey City, and in 1888, the city acquired the eastern section of the Lorillard lands for incorporation into Bronx Park. The western section—today’s Belmont—was subdivided for development. Many Italian immigrants were attracted to the area by jobs in the construction of the New York Botanical Garden (opened 1891), the Bronx Zoo (opened 1899) and the Jerome Park Reservoir (opened 1906). There is a persistent myth that Arthur Avenue was named by one of the Lorillards in honor of President Chester A. Arthur. However, the name “Arthur Street” appears on the New York City Department of Public Parks topographical map of the Bronx in 1873. That is eight years before Arthur became president, making it unlikely that the avenue was named for him.

To learn more about the area, visit www.BronxLittleItaly.com.

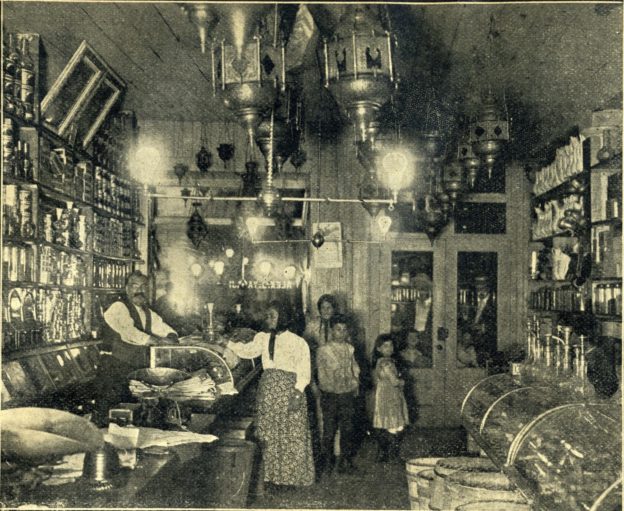

Originally called District Street, Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn is one of the borough’s most dynamic commercial thoroughfares. There, within a cohesive mid-19th century streetscape, one can shop for one-of- a-kind home treasures, stock up on Middle Eastern food delicacies, and meet friends for dinner and drinks. Underfoot is the world’s first subterranean train tunnel, which was rediscovered in 1980.

To learn more about Atlantic Avenue click here

The beginnings of the community now known as Audubon Park date back to 1841, when John James Audubon purchased fourteen acres and built a large mansion along the Hudson River shortly after publishing his famous work, Birds of America. Audubon named his farm, a pastoral landscape of woods, wildlife and rocky outcroppings, “Minnie’s Land” in honor of his wife. After bringing back plant and animal specimens from his 1843 expedition to the American West, Audubon lived on this secluded estate until his death in 1851. Facing financial hardship, Audubon’s family sold the land in small portions through the 1850s and 1860s. As early as 1854, the name Audubon Park was used for an enclave of ten large homes located on the former estate. Into the 1890s, Audubon Park retained a distinct identity from that of the rest of Washington Heights, remaining relatively secluded even as improvements in the street system and the introduction of cable cars and the Ninth Avenue elevated railroad brought residential development to its borders. In 1892, the city extended its fire limits up to West 165th Street, prohibiting new wood frame construction. The first masonry structures to appear within Audubon Park were a row of 12 three-story rowhouses constructed in 1896-98 on West 158th Street.

When the Interborough Rapid Transit subway line along Broadway arrived at West 157th Street in 1904, Audubon Park was ripe for explosive growth. In 1905, the first apartment buildings in the area were built just outside Audubon Park’s boundaries at 609 West 158th Street and 3750 Broadway. However, most development occurred after the Grinnell family, which had controlled most of the former Audubon estate since the 1880s, sold its holdings to a syndicate of developers in 1908. Within a year, nine apartment buildings replaced most of the area’s winding roads and wood frame villas. From 1905 to 1932, 19 apartment houses were constructed in what is now the Audubon Park Historic District. Elegantly designed in a variety of styles and equipped with modern amenities, these buildings were marketed for upper middle-class tenants. Anchoring this neighborhood was Audubon Terrace, a unique complex of educational and cultural institutions whose construction began in 1904 and included the Church of Our Lady of Esperanza and the Hispanic Society of America. The influence of Audubon Terrace on the surrounding neighborhood is reflected in the names of some of its apartment buildings, including the Cortez, Goya, Hispania and Velazquez.

Audubon Park has served as the site of significant preservation battles throughout its history. Efforts to create a park out of the remaining undeveloped portions of the Audubon estate and to save the John James Audubon house as a museum were scuttled by the construction of a viaduct carrying Riverside Drive from 151st Street to 161st Street in 1928. With the imminent development of new apartment buildings, a local community group successfully moved the house, but it was eventually demolished despite these efforts. Fortunately, success stories can be found in the designation of the Audubon Terrace and Audubon Park Historic Districts in 1979 and 2009, respectively. Today, a group of residents working with the Riverside Oval Association is advocating for the protection of the aforementioned 12 rowhouses on West 158th Street, constructed in 1896-98.

Initially developed as a suburban enclave for Brooklyn’s business elite in the decades following the Civil War, Bay Ridge transformed into one of the borough’s most culturally diverse neighborhoods with the arrival of the IRT subway in 1916 and it remains so today. Visitors to this neighborhood will find vibrant commercial districts, cohesive rowhouse blocks, wood frame farmhouses, Victorian mansions, beautiful churches, pre-war apartment buildings, and quaint cul-de- sacs.

To learn more about Bay Ridge click here

Dating back to 1831, the Bayley Seton Campus was Staten Island’s first public health facility, originally known as Seaman’s Retreat. The original Seaman’s Retreat building is a designated NYC landmark that is seriously threatened by demolition by neglect. The site also contains the first U.S. Public Health Service Hospital, a Mayan Revival style building built in 1931, and smaller contributing doctors residences. Working with John P. Kilcullen of the Preservation League of Staten Island, HDC will help advocate for landmarking, stabilization, and preservation of the hospital complex.

Since 1984, the Bayside Historical Society (BHS) has been located at The Castle in Fort Totten Park. Built in 1887, the building was originally used by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers as their Officers’ Mess Hall and Club. The Gothic Revival-style Castle is a NYC designated landmark and is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

HDC is partnering with the Bayside Historical Society to build on their work since the 2016 designation of the Ahles House and continue surveying, researching, and compiling a list of significant sites for consideration for preservation and designation.

In the 1850s, the neighborhood now known as Bedford Park was part of the property owned by financier and noted sportsman Leonard Jerome, Winston Churchill’s grandfather. He leased a section of it for use as a race track and, to ensure accessibility and promote development, lobbied for a paved boulevard and began selling off his other Bronx properties. By the 1870s, streets were laid out and blocks were subdivided into house lots, but construction didn’t take off until the early 1880s. Early developments were primarily free-standing wood-frame homes, soon followed by religious architecture and infrastructure. Some of the oldest surviving examples of these buildings include houses at Bainbridge Avenue & E 201st Street, the Bedford Park Congregational Church, the Convent of Mount St. Ursula and the former Beford Park Railroad Station .

By the early-20th century, transportation improvements such as the extension of elevated lines to nearby Fordham Road, and construction of the Mosholu Parkway, had expanded the boundaries of the neighborhood and increased the population drastically. This fueled residential development and also prompted the construction of new facilities for city services, like the NY Fire Department and the NYPD . Several prestigious educational institutions were also created, with buildings located in an area referred to as the Educational Mile. These include DeWitt Clinton and the Bronx High School of Science, along with Lehman College.

However, the most significant project in the neighborhood’s development was the construction of the Jerome Park Reservoir, transforming the former racetrack at Jerome Park into a fresh-water reservoir for the New Croton Aqueduct. Completed in 1906, it became a valuable asset for the rapidly growing City of New York and provided residents with recreational open space. The project also shaped demographics, as the Italian and Irish immigrants who worked on it relocated to the area and built neighborhood staples like the St. Philip Neri Roman Catholic Church.

Bedford Park continued to grow throughout the 20th century, especially after WWI. During this time, it began to shift from a quiet suburb into a more densely populated urban area. Within 20 years of the completion of the Grand Concourse, apartment buildings featuring the then fashionable architectural styles lined the boulevard and the surrounding areas, replacing single-family houses. This type of development would continue throughout the 1950s, but the neighborhood never lost its bucolic character and ethnic diversity.

Today, Bedford Park is facing significant development pressures, with many of the early free-standing houses already lost to out-of-scale development. Community groups and organizations are working to raise awareness on the area’s history and significance, in order to protect its character and the neighborhood from.

The majority of the buildings were constructed on speculation to house New York’s growing middle class, generally between 1870 and 1920. Rowhouses are set back from the street and possess their original stoops and railings. The architectural style of buildings followed the trends popular during the area’s development, including Italianate, Neo-Grec, Romanesque Revival, Queen Anne, and, at the turn of the 20th century, Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Georgian appeared. The materials of the buildings also give an idea of their age; older buildings were constructed of brick and brownstone, while light-colored brick, terra-cotta and limestone became increasingly popular toward the turn of the 20th century.

Stuyvesant Heights in Bedford-Stuyvesant was designated a New York City historic district in 1975, and a large extension was designated in 2013; the Bedford Historic District was designated in 2015. The low-scale buildings on the tree-lined streets share architects, styles and details, together making Bedford-Stuyvesant a distinctive piece of New York City.

To learn more about Bedford-Stuyvesant click here

HDC will help the Bushwick Historic Preservation Association advance their proposed list of landmark designations and preservation priorities, including the Northeast Bushwick Historic District.

While Park Slope has received the protection of landmark designation in certain areas, the historic heart of the neighborhood remains at risk of new development and drastic alterations. A special committee of the Park Slope Civic Council is working to expand the Park Slope Historic District and to ensure the preservation of the Center Slope, an area with spectacular brownstones and ties to the American Revolutionary War. From community outreach to survey endeavors, this group is aiming to work towards completing the quilt of landmark protections for the Park Slope neighborhood.

In 1750, British naval officer Thomas Clarke bought a Dutch farm to create his

retirement estate, named “Chelsea” after the Royal Hospital Chelsea in London. His

property extended from approximately Eighth Avenue to the Hudson—its shore ran

roughly along today’s Tenth Avenue—between 20th and 28th Streets. The estate

was subdivided in 1813 between two grandsons; Clement Clarke Moore received the

southern half below 24th Street while his cousin, Thomas B. Clarke, inherited the

northern section.

In the 1830’s, as the street grid ordained by the city in 1811 extended up the island

and through his property, Moore began dividing his land into building lots for sale

under restrictive covenants which limited construction to single-family residences and

institutional buildings such as churches. By the 1860’s, the area was mostly built out with

a notable concentration of Greek Revival and Anglo-Italianate style row houses, many

now preserved within the Chelsea Historic District.

Thomas B. Clarke’s property north of 24th Street was developed around the same time,

but with a more varied mixture of row houses, tenements, and industry. By the late

19th century, the area had an unsavory reputation. During the urban renewal era of the

mid-20th century, much of it was officially declared a slum and rebuilt with tower-inthe-

park housing, although clusters of row houses and several significant institutional

buildings remain.

By the 1850’s, infill of the Hudson pushed the waterfront to Eleventh Avenue and

within decades to its current location west of Twelfth Avenue. Industry was bolstered

by the mid-19-century with the opening of the Hudson River Railroad, and soon the

neighborhood supported a range of smaller manufacturers interspersed with sizable

operations including iron works and lumberyards. Storage and warehousing became

important uses around the turn of the century with the creation of the Gansevoort

and Chelsea Piers. By 1920, most of the area’s factories had been replaced by modern

facilities. The heart of this industrial district is preserved within the West Chelsea Historic

District. Clement Clarke Moore’s rowhouse blocks to the east were largely converted to

apartments for a working class employed by these businesses. As they became inactive,

an influx of gay residents opened a new chapter of Chelsea history. The neighborhood

remains proudly gay friendly today.

The current character of the western part of Chelsea is built on adaptive reuse of

industrial relics. Art dealers drawn to the lofty spaces of former warehouses and factories

began arriving in the 1990’s and built the blocks west of Tenth Avenue into the world’s

largest gallery district. After decades of abandonment, the elevated Hudson River

Railroad was transformed into the High Line, a public park and tourist attraction. Its

innovative design and impact on real estate values spurred a boom in new buildings by

celebrated architects along its length.

Although Thomas Clarke’s 1750 Chelsea estate extended only east to Eighth Avenue

and south to 20th Street, the present-day neighborhood encompasses a larger area.

Its eastern edge along Sixth Avenue lies within the Ladies’ Mile Historic District, named

for the elite shopping district, which saw its first department store open in the 1860’s.

Today, Chelsea contains a variety of historic architecture, including some of the city’s

most intact nineteenth-century residential blocks, significant commercial buildings, and

industrial complexes near the Hudson River.

Chinatown and Little Italy, Manhattan

Two adjoining and overlapping iconic communities that represent the country’s immigrant history in the national consciousness, Chinatown and Little Italy are seeing the loss of legacy businesses and insensitive alterations to historic storefronts and tenement facades. The Two Bridges Neighborhood Council is working to raise public awareness of the area’s history and architecture, to promote the neighborhoods as historic resources, to educate property owners on appropriate and sensitive building renovations and to gain protections for area landmarks such as the Lefkowitz building, recently proposed as the site of a new jail facility.

*Photo credit – Flickr Larry Gassan

While just nine blocks apart from one another, Clay Avenue and the Grand Concourse appear to be worlds apart in terms of architecture and urban form. However, both the small-scale street of two-family houses and the wide thoroughfare lined with Art Deco apartment buildings help to tell the story of the development of this section of The Bronx. Both are located in what was historically the village of Morrisania, named for the English brothers Colonel Lewis Morris and Captain Richard Morris who purchased the land in 1670.

In 1900, Ernest Wenigmann began amassing property on Clay Avenue with the intention of constructing 28 houses. Wenigmann commissioned architect Warren C. Dickerson, who had a reputation for designing many fine rowhouses across the borough. For the Clay Avenue development, Dickerson employed elements of the Renaissance Revival and Romanesque Revival styles, and while the houses are all different in their ornamentation, they are linked by the use of beige or red brick, as well as their similar massing and repetitive trends found on either side of the street. The houses were designed in pairs, with each house meant to house two families, but Dickerson subtly designed the houses so that each would give the appearance of a single-family dwelling. Thus, the aspirational middle-class homeowner could fit their family into one apartment while renting out the adjacent unit for additional income, all the while residing in what appeared to be a single-family home. The 28 houses on Clay Avenue were all constructed between 1901 and 1902, when Ernest Wenigmann began selling the properties. Within three years, the street was almost entirely occupied, illustrating the success of Wenigmann’s venture and Dickerson’s designs. Clay Avenue remains a beloved architectural ensemble and tight-knit community.

In 1909, seven years after Wenigmann completed construction of the houses on Clay Avenue, the Grand Concourse was opened to traffic and became a crucial link between Manhattan and the still rural sections of The Bronx. The completion of the Jerome Avenue subway in 1918 and the introduction of real estate tax exemptions precipitated a wave of development that swept the Grand Concourse from 1922 to 1931. This period saw the construction of over half of the district’s buildings, primarily five- and six-story apartment houses situated on large lots and enlivened by decorative elements that evoked faraway places. The 1933 opening of the IND subway along the Grand Concourse sparked a second building boom from 1935 to 1945 that produced many now iconic Art Deco and Moderne style buildings. These structures feature terra cotta, mosaic tile, cast stone and beige brick in their designs. Although these buildings were executed in a range of architectural styles, many of them are representative of the garden apartment typology. This housing form, which developed in the late 1910s and 1920s, was principally characterized by medium-rise structures arranged around large courtyards.

The neighborhoods surrounding Clay Avenue and the Grand Concourse shared in the precipitous population loss and economic decline that plagued much of The Bronx in the post-World War II era. Nevertheless, the community emerged from the turmoil to become the stable, dynamic and diverse area that it is today. The significance and integrity of this neighborhood’s built fabric prompted the Landmarks Preservation Commission to designate two historic districts here: Clay Avenue (1994) and the Grand Concourse (2011).

The area of Queens comprising Corona-East Elmhurst was called “Mespat” by the Native Americans and “Middleburgh” by the English colonists. It became part of the Town of Newtown, when it was incorporated in 1683 as one of the three original municipalities (along with Jamaica and Flushing) comprising what is now Queens. It remained largely rural until transportation improvements led to suburban development. In 1854 the Flushing Railroad began service through what is now 44th and 45th Avenues (now part of the Port Washington Branch of the Long Island Rail Road). Anticipating commuter service, a group of real estate speculators formed the West Flushing Land Company and purchased an extensive tract that they subdivided into house lots, naming the new neighborhood West Flushing. Just north (above what is now 37th Avenue) stood the National Race Course, also established in 1854. A massive complex and tourist attraction, it was soon renamed Fashion Race Course and notably hosted the first-ever ticketed baseball game, a best of three series between New York and Brooklyn.

In spite of this enthusiasm, actual building activity remained slow through the 1850s and was curtailed during the Civil War. By 1868, however, Benjamin W. Hitchcock, who also developed much of Woodside, acquired more than a thousand building lots in West Flushing, and most were sold by the early 1870s. Another local developer, Thomas Waite Howard, felt the name West Flushing was too easily confused with Flushing and petitioned the U.S. Postal Service for a more poetic moniker: Corona, the crown (or crown jewel) of Queens. Transit lines continued to expand, including the 1876 introduction of horse car lines to Brooklyn, providing connections to ferries to Manhattan, and trolleys running along Corona Avenue began in the 1890s. In 1898 Queens County was subsumed into Greater New York, and Corona, previously part of Newtown, became its own neighborhood with 2,500 residents. In 1904 the Bankers’ Land and Mortgage Corporation launched a new residential development in north Corona called East Elmhurst, comprising 2,000 building lots along the western edge of Flushing and Bowery Bays. Growth accelerated with the opening of the Queensborough Bridge in 1908 and the East River tunnels to Pennsylvania Station in 1911. Perhaps most significantly, the subway system arrived in 1917 with the opening of the Alburtis Avenue (now 103rd Street-Corona Plaza) station. In the 1930s the neighborhood’s eastern boundary, the dumping ground that was once Flushing Creek, was transformed into “The World of Tomorrow” as the site of the 1939 World’s Fair; it later reprised that role for the 1964 World’s Fair and eventually became Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

From the beginning, Corona-East Elmhurst was a diverse neighborhood. Several of its oldest institutions attest to the 19th century German influence, while many 20th century sites are associated with its Italian-American and Jewish communities. The northern section of this tour boasts a remarkable collection of culturally significant African-American sites. The first recorded residents of African descent arrived in the 17th century and settled along what is now Corona Avenue, a section of which (at 90th Street in Elmhurst) is named for the Rev. James Pennington (1807-1870), an enslaved fugitive from Maryland who became an influential Evangelical Abolitionist on the world stage. In the 1920s, Corona saw an influx of African-Americans, many following the Great Migration from the South, and Afro-Caribbean immigrants from the West Indies. After World War II, the area attracted prominentAfrican-American cultural figures and civil rights activists, many of whom are celebrated on this tour.

The Crown Heights North Association (CHNA) is dedicated to the preservation of the historic buildings of the Crown Heights North community in Brooklyn. Its focus is the revitalization, economic advancement, housing stabilization, and cultural enhancement of the area’s residents. The group is particularly concerned with new construction taking place on Franklin Avenue. Working with HDC, CHNA plans to educate residents on the landmarking process, as well as highlighting buildings within the proposed Phase 4 of the Crown Heights North Historic District, including St. Marks Avenue, Dean, Bergen and Pacific Streets and the enclaves of St. Francis and St. Charles Places, between Bedford and Franklin Avenues.

From farmland before the 1850’s, Crown Heights grew into one of Brooklyn’s most architecturally distinguished neighborhoods within less than 50 years and was recognized with historic-district designation in 2007. Originally part of Bedford-Stuyvesant and known as Bedford, it adopted the name “Crown Heights” in the mid-20th century. Today it is strongly Caribbean- and African-American with a growing white population.

To learn more about Crown Heights North click here

Located along the hilly terminal moraine between the prosperous communities of Bedford and Flatbush, Crown Heights South was considered a rocky no-man’s land of scrub farmland for most of the 19th century. During that time, it was home to subsistence farmers whose homes dotted the landscape, as well as poor Irish and black families who settled in shantytowns called “Crow Hill” and “Pigtown” by a derisive press. In 1846, this was where the city of Brooklyn placed the Kings County Penitentiary, as far from downtown Brooklyn as was feasible.

By 1874, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux had completed Eastern Parkway as a Parisian-style boulevard to extend the picturesque character of Prospect Park into the expanding residential neighborhoods of Brooklyn. The parkway, which followed the moraine through the neighborhood that was now called Crown Heights, was designed to be lined with fine homes and mansions, though this housing never developed as Olmsted and Vaux envisioned. The thoroughfare did bring attention to the neighborhood, though, and formed the border between Crown Heights North and Crown Heights South in later years. While the northern side of Crown Heights was fully built up by 1900, it wasn’t until after the new century began that large-scale residential development began in southern Crown Heights. The north-south corridors of Nostrand, Bedford, Rogers and Franklin Avenues were already important transportation corridors, leading to the paving of Union, President, Carroll and other cross streets.

Several major changes led to the development of Crown Heights South after the turn of the 20th century. These included the 1907 demolition of the infamous Kings County Penitentiary, which was replaced by a Jesuit Prep school and college; the 1913 construction of Ebbets Field, home to the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team; the development of Brooklyn’s famous Automobile Row, with its showrooms and service centers, which flourished on Bedford Avenue between 1905 and 1945; and the presence of the nearby Brooklyn Museum, which opened in 1897. Encouraged by these developments, as well as the new subways constructed under Eastern Parkway, developers built up entire blocks at a time with new housing. With the exception of certain blocks of single-family mansions, much of what was built was designed for multiple families, as the age of the single-family rowhouse had nearly passed. Crown Heights South displays a fine array of architectural styles of the early 20th century, designed by such prominent Brooklyn architects as Montrose W. Morris, Axel Hedman, J. L. Brush, Arthur Koch and Slee & Bryson in the Revival styles popular at the time: Renaissance, Colonial, Flemish, Tudor and more.

Today, the neighborhood retains its vibrant mix of residential architecture, including attached rowhouses, detached mansions and grand apartment buildings, as well as some fine religious buildings and grand institutions. One of its most well-known structures is the Bedford Armory, the city’s first mounted cavalry-unit armory that occupies an entire city block. The armory’s future is a source of controversy, with developers seeking to construct housing on the site and community members vying to preserve the building. Unfortunately, none of Crown Heights South’s architectural gems have been designated as landmarks by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Local advocates, including the Crown Heights South Association, formed in 2016, are working to survey and advocate for the neighborhood to ensure that any future changes are sensitive to its rich past.

New York City is known for many things: Art Deco skyscrapers, picturesque parks, the world’s greatest theater district, venerable museums and educational institutions, not to mention bagels and pizza! But above all of these, New York is most important as home to some of the world’s most fascinating and significant people and as the site of impactful and significant happenings throughout history. The city’s cultural influence is, perhaps, its greatest contribution to the world, and its built environment stands as a grand scavenger hunt of clues waiting to be uncovered. Lucky for us, the city’s Landmarks Law, passed in 1965, provides the legal framework for protecting the physical reminders of the city’s cultural wealth. In fact, one of the stated purposes of the Landmarks Law is to “safeguard the city’s historic, aesthetic and cultural heritage.”

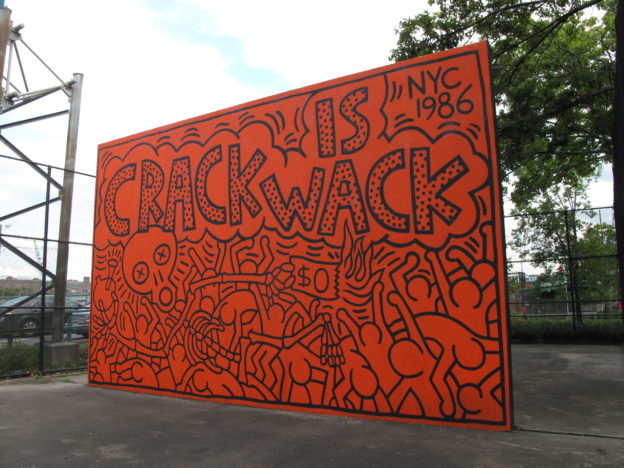

In the first 50 years that landmarks were designated by the City, much emphasis was placed on the historic and aesthetic. In recent years, though, more consideration has been made for the importance of sites associated with people or historical events, rather than just for their architectural or historical value. In 2015, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the Stonewall Inn as an Individual Landmark solely for its association with the Stonewall Uprising of 1969. In 2018, the Commission designated the Central Harlem—West 130th-132nd Streets Historic District, describing it as “not only representative of Central Harlem’s residential architecture, but the rich social, cultural, and political life of its African American population in the 20th century.” Also, in recent years, Greenwich Village’s Caffe Cino and Julius’ Bar were listed on the National Register of Historic Places as significant and influential sites connected to the Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender (LGBTQ) community, The New York Times profiled a historian giving tours of Muslim sites of significance in Harlem, and the City is commemorating some of our most storied and accomplished female citizens with the installation of statues in all five boroughs. Indeed, grassroots preservation activism around the city is also swelling around sites of cultural significance: Tin Pan Alley and Little Syria in Manhattan, Walt Whitman’s house in Brooklyn, Arthur Avenue in The Bronx and a recently-rediscovered African burial ground in Queens, to name a few.

In response to this movement of interest in cultural landmarks, the Historic Districts Council undertook an initiative to highlight such places as one of its Six to Celebrate in 2018. The culmination of that effort was a conference in October 2018 entitled “Beyond Bricks and Mortar: Rethinking Sites of Cultural History.” The conference convened preservationists, historians, artists, planners, place-makers and more to work together to clarify what cultural significance is and how it can work, how to document and create compelling narratives around cultural sites, and how to identify the specific challenges of cultural sites from a preservationist perspective.

This brochure provides just a sample of some of the city’s cultural landmarks, organized thematically and representing all five boroughs. The list includes some sites that are legally protected — in some cases by more than one government body — and some that are unfortunately in danger of being lost. Preserving culturally significant sites that may not possess overtly aesthetic value often requires a particularly active and engaged form of advocacy to achieve protection from the wrecking ball. But, as long as there are interesting people making their mark on New York City and crucial events taking place here, that effort will never be in vain, since those stories are the lifeblood of this vibrant place.

Dorrance Brooks Square, Manhattan

A residential enclave, this neighborhood east of St. Nicholas Park features remarkably intact and finely detailed residential rowhouse architecture, built for upper-middle-class professionals in the late 19th century. The community is named for the adjoining park dedicated in 1925 that honors African-American infantryman Dorrance Brooks, who displayed ”signal bravery” in World War I. The square became a rallying point for civil rights protests. Closely associated with the Harlem Renaissance, the area was home to jazz musician Lionel Hampton. The Dorrance Brooks Property Owners and Residents Association is seeking official recognition of and protection for its historic character and buildings.

The Downtown Brooklyn Landmarks Coalition, which is made up of the Park Slope Civic Council, the Brooklyn Heights Association, Cobble Hill Association, Prospects Heights Neighborhood Development Corporation, Friends of Terracotta, DUMBO Neighborhood Association, and the Boerum Hill Association was created in 2023 in response to the rapid development occurring in Downtown Brooklyn. The coalition aims to identify buildings worthy of designation to preserve the historic and cultural significance of the neighborhood before it is lost.

HDC will assist the Downtown Brooklyn Landmarks Coalition with strategies and publicity to advance their landmarking campaign for significant buildings and sites in Downtown Brooklyn.

East Flatbush is not only rich in historic character but in nature as well! Sitting within its boundaries is the award-winning “Greenest Block in Brooklyn”, East 25th Street, a block that teems with greenery and community enthusiasm. From churches to Neo-Renaissance rowhouses, the 300 East 25th Street Block Association is working to celebrate and preserve the structures in their unique community and to oppose the threats of demolition and overdevelopment. This group is seeking official recognition and protection of the area by being designated a historic district.

UPDATE:

The East 25th Street Historic District was designated on November 17, 2020

East Harlem encompasses a large section of northeastern Manhattan bounded by 96th Street, 142nd Street, Fifth Avenue and the Harlem River. Also known as El Barrio, the area is famous as one of the largest predominantly Latino neighborhoods in the city.

Echoing development patterns across the city, the neighborhood was largely built in response to the availability of transportation. In the 1830s, tracks were laid along Park Avenue for horse-drawn streetcars and later, the tracks became the New York and Harlem Railroad line, with train stops in East Harlem Development was relatively slow until the construction of the Second and Third Avenue elevated rail lines to 125th Street in 1879-80, followed by a second wave of development with the arrival of the subway in 1919. Rowhouses, tenements and flats buildings housed the area’s largely working class population, while Third Avenue became the area’s first commercial thoroughfare.

To learn more about East Harlem click here

East Harlem abarca una larga parte del noroeste de Manhattan, delimitado por 96th Street, 142nd Street, la Quinta Avenida y el Río Harlem. También conocida como El Barrio, esta área es famosa por ser uno de los barrios con más latinos en la ciudad.

Repitiendo los patrones de urbanización de la ciudad, el barrio fue mayormente construido en respuesta a la disponibilidad de transporte. En la década de 1830, se construyeron rieles a lo largo de Park Avenue para tranvías impulsados por caballos. Los rieles se convirtieron en la vía férrea de Nueva York y Harlem, con paradas en East Harlem (vea sitio #5a). Varios hoteles fueron construidos para aprovechar las elevaciones de altura que ofrecían vistas de la creciente ciudad hacia el sur y se construyeron haciendas residenciales en la zona costera. La urbanización aumentó con la construcción de las vías férreas elevadas de la Segunda y Tercera Avenida hasta 125th Street entre 1879 y 1880, y con la llegada del subterráneo en 1919. Casas en hilera, conventillos y edificios de apartamentos albergaron a gran población de clase trabajadora, y la Tercera Avenida se convirtió en su primera avenida comercial.

East New York is a dynamic and largely unrecognized jewel in New York City. In the mid-17th century, Dutch farming families began migrating here from the town of Flatbush, referring to the land as the “new lots,” and it was soon identified as a subsidiary of Flatbush. In 1852, residents deemed themselves independent and began to refer to the community officially as New Lots. Present-day East New York is part of what was once the town of New Lots. In 1886, New Lots was annexed to help form the city of Brooklyn, and in 1898, was annexed again when Brooklyn and the other boroughs were consolidated to become the City of Greater New York.

In 1835, developers began buying farms in New Lots and laying out streets and lots. The area was prime for development due to the presence of the Jamaica Turnpike and the Long Island Railroad tracks along Atlantic Avenue. It was also a well-known destination for its two horse racing tracks, Union Course and Centerville Race Track (both demolished). The area’s most influential developer was a Connecticut merchant named John Pitkin, who purchased 135 acres and named his neighborhood East New York. The renaming was not only to set it apart for real estate purposes, but Pitkin envisioned a world-class and impressively-designed community filled with factories, shops and housing to rival New York City – an illustrious goal. Although Pitkin experienced significant losses during the financial panic of 1837, sales picked up in the mid-19th century and East New York became a thriving community even before neighborhoods much closer to Manhattan had even begun to be developed. Transportation improvements in the 1880s, including the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge and the introduction of steam cars and the elevated railroad on Atlantic Avenue, led to a building boom in East New York. Immigrants, including Germans, Italians, Russians and Eastern Europeans, migrated from crowded Manhattan neighborhoods to settle in the East New York countryside, in hopes of building a community where they would be free to communicate in their native languages, congregate and worship, patronize businesses catering to their cultural tastes and provide their children with opportunities to become skilled and educated citizens.

By the 1930s, East New York was widely regarded as a stable, working class community, boasting of great housing stock, schools and low crime. After World War II, however, the neighborhood unfortunately experienced a slow decline that it is still recovering from today. After the war, the city lost a great number of manufacturing jobs at the same time as large numbers of Puerto Ricans and African Americans were arriving in the city seeking employment. East New York was hit particularly hard in the 1970s by the FHA Mortgage Scandal and the unscrupulous and racially-charged real estate practice of “blockbusting,” which resulted in home foreclosure and abandonment. Unemployment, drug abuse and crime became commonplace in East New York, and its notorious reputation unfortunately lingers today. In recent years, East New York has begun to experience a rebirth. Vacant lots have been transformed into community gardens; well-maintained homes have helped to revitalize blocks; desolate sections under the elevated train tracks now exhibit vibrant murals; and diverse groups are working to enhance the neighborhood. One of these is Preserving East New York, a grassroots preservation group that formed to protect the neighborhood’s historic resources and illuminate its 300-year narrative of refuge, expansion, battle and rebirth. The group is advocating for landmark designation of some of the area’s historic buildings, an effort mainly spurred by the city’s announcement in 2015 that East New York would be rezoned for increased density as part of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s Housing New York plan.

Historically, the Lower East Side extended from East 14th Street south to Fulton and Franklin Streets, and from the East River west to Broadway and Pearl Street. Today, the regarded boundaries of the East Village and Lower East Side extend roughly from East 14th Street to the Bowery to the East River, with Houston Street as their north-south divider.

The area’s architecture reflects its early development, with extant examples of early 19th century rowhouses, religious structures, theaters, schools, libraries, banks and settlement houses and the tenement. The East Village contains three New York City historic districts: St. Mark’s Historic District and Extension, East Village / Lower East Side Historic District and East 10th Street Historic District. The latter two were designated in 2012 after a robust advocacy and outreach effort by community groups and preservationists. At the time of this publication, there are no locally designated historic districts in the Lower East Side.

To learn more about East Village/Lower East Side click here

The first European settlement in Elmhurst was founded in 1642 at the head of the Maspeth Creek. The town was destroyed due to increasing conflicts between Native Americans and the Dutch, and was replaced in 1652 by a new village located on safer ground inland, at what is now Queens Boulevard and Broadway. The English called the place Middelburgh, since Dutch authorities required a Dutch name, but referred to it as Newtown among themselves, to distinguish it from the old town at Maspeth.

The 18th century was a period of prosperity for Newtown Village, population slowly increased and the local economy became more diversified. The proximity to New York allowed for crops to be sold in the open market or traded for manufactured goods, and also provided access to luxury goods and services. The road system was largely created during this time, connecting the outlying hamlets with the churches and town offices at Newtown, giving them access to the mills, the meadows and the shore. During the Revolution, the British Army occupied Newtown. Officers were billeted in the houses and buildings were repurposed for field hospitals, armories and headquarters. After the war, the town recovered gradually, mostly thanks to new practices and technologies in agriculture that boosted the economy. Social change was spurred by the abolition of slavery in New York State in 1827 and a group of newly freed African Americans established the first African Mehtodist Episcopla (A.ME.) Church and cemetery in the town.

In the years before the Civil War, and during the first decade after, Newtown remained largely a one-street town. Although there was some commercial growth, and a new building was erected for the Newtown High school (site 6), attempts to expand the limits of the old village were unsuccessful. This began to change in 1869, when large estates were auctioned. In 1893, the Meyer brothers, led by Cord Meyer Jr., bought over 100 acres of the Samuel Lord estate to develop an ambitious plan for a new suburb northwest of the old Newtown Village. This development was planned to offer amenities rarely present in a rural district, and certainly nowhere else in Queens at the time: paved streets, a water system and private sewers. The project proved to be extremely successful, and the neighborhood became known for its fashionable housing developments and infrastructure. Cord Meyer, Jr. also lobbied to have the name of the village changed to Elmhurst, to avoid any association with the polluted Newtown Creek. The name is said to have been inspired by large, mature American elms that existed along Broadway, particularly in front of St. James Church. Despite initial resistance from the townspeople to discard the historic name of the village, in 1896 the Post Office officially changed to Elmhurst.

The opening of the subway in 1936 spurred local development which resulted in the destruction of much of the old village’s building stock, most notably the Moore Homestead. After the Second World War, Elmhurst became a place for architectural innovation. Influenced largely by the New York World’s Fair of 1964, buildings like the Pan American Hotel, the Queens Place Mall and the former Jamaica Savings Bank branch (site 15) changed the neighborhood’s landscape. In the 1980s, immigrants from many different countries changed Elmhurst from an almost exclusively white community to the most ethnically diverse neighborhood in the city.

In the early 20th century, a thriving network of vacation communities was constructed along the oceanfront in Brooklyn and Queens to accommodate the city’s working class in their summertime recreational pursuits. One of these was Rockaway, Queens, which was once home to over 7,000 modest bungalows in dozens of distinct seasonal communities. Sadly, fewer than 400 exist today, the rest having been demolished to make way for new development beginning in the mid 20th century. Rockaway’s largest cluster of existing bungalows (93 in total), located in Far Rockaway on Beach 24th, 25th and 26th Streets south of Seagirt Avenue, was once part of a Russian and German Jewish immigrant community called Wavecrest.

To learn more Far Rockaway Beachside Bungalows click here

One of the first Queens residential developments was Forest Hills, a 600-acre parcel of farmland previously known as the Hopedale section of Whitepot. Purchased by the Cord Meyer Development Company in 1906, the parcel was renamed in honor of its proximity to Forest Park and its elevation above the surrounding area.

For this new development, George C. Meyer stipulated the layout of a suburban community, with lots designated for houses, schools and churches, as well as utilities and plantings. Aesthetically, the area would be united by its architecture. Meyer hired architects Robert Tappan and William Patterson to design single-family houses that would complement one another. Cord Meyer began the development of these lots in 1906, mostly north of Queens Boulevard. Forest Hills Gardens was established in 1909, and the community was completed in 1912-13. Arbor Close and Forest Close, small townhouse complexes with shared gardens, were constructed in 1925 and 1927, respectively.

To learn more about Forest Close & Forest Hills click here

HDC will help the Fort Washington Historic District Task Force advocate for community preservation efforts, including a Fort Washington Historic District that includes a stylistically diverse and well preserved stock of the early twentieth-century apartment complexes, which are a character-defining feature of the neighborhood, as well as sites significant to the area’s Jewish heritage.

HDC will support the Garifuna Coalition USA, Inc., an organization representing a culturally differentiated Afro-indigenous community who began migrating to New York City in the 1930s, in their efforts to be more effective in their strategy to identify the historic resources in their community and promote the community’s significance.

The New York Fashion Workforce Development Coalition (NYFWDC) is a multi-stakeholder working group bringing together individuals from the fashion industry, community, academia, non-profit sectors, and government to find solutions to strengthen and grow New York’s fashion future via social justice, women’s economic advancement and empowerment.

HDC is supporting the NYFWDC in their efforts to promote the Garment District’s cultural, historical, and architectural significance and advocate for the continued presence of fashion manufacturing within the district as part of larger plans for the area.

The Brooklyn community of Gowanus, centered around the Gowanus Canal, is largely made up of historic architecture directly related to the water route. Located between Park Slope and Carroll Gardens, it is considered part of Brooklyn’s industrial waterfront. The canal itself is 2.5 miles long, 100 feet wide, and stretches from Gowanus Bay in New York Harbor to Douglass Street. Unlike other industrial areas of the city, Gowanus was never densely built up, and much open space remains today. The structures that surround the canal are generally six stories or fewer, lending a low-scale, 19th-century character. This area continues to be mixed-use manufacturing with peripheral residential enclaves.

Historically one of New York’s most contaminated waterways, the Gowanus Canal area was designated as a Superfund Site in 2010. To protect the historic character of the neighborhood the local community is currently working to place the Gowanus Canal Corridor on the National Register of Historic Places so that its urban industrial character is preserved.

To learn more about Gowanus click here

Spurred by a period of economic growth and an influx of European immigrants during the 1850s, more than a dozen shipbuilding firms turned the neighborhood into a major shipbuilding center. While shipbuilding declined after the Civil War, Greenpoint’s other industrial enterprises, which included porcelain making, glass making, and oil refining, continued to thrive. Greenpoint’s residential development was closely aligned with its industrial growth, as workers’ housing was built inland from the waterfront. Large, elaborate rowhouses were constructed for owners and managers, while modest rowhouses, tenements, and apartment buildings were built for laborers. The neighborhood also boasts many fine churches and institutional buildings, such as the Greenpoint Savings Bank and the Mechanics and Traders Bank.

To learn more Greenpoint click here

This single-block street in the north shore neighborhood of Stapleton encapsulates Staten Island’s 19th century residential character, projecting a strong sense of place. It features a rare grouping of intact wood frame and masonry houses, many boasting whimsical architectural features. At this time, there are just three historic districts on the whole island.

To learn more about Harrison Street click here

municipal cemetery in the United States. It was part of the property purchased by the English physician Thomas Pell from Native Americans in 1654. On May 16, 1868, the Department of Charities and Correction (later the Department of Correction or “DOC,” which split off from the Department of Public Charities in 1895), purchased Hart Island from the family of Edward Hunter to become a new municipal burial facility called City Cemetery. Public burials began in April 1869. Since then, well over a million people have been buried in communal graves with weekly interments still managed by the DOC. The burials expanded across the entire island starting in 1985. Over its 150-year municipal history, it has also been home to a number of health and penal institutions. The island is historically significant as a cultural site tied to a Civil War-era burial system still in use today.

During the Civil War, in April 1864, the federal government leased Hart Island as a training camp for the 31st regiment of the United States Colored Troops. For four months in 1865, Hart Island was host to a prisoner-of-war camp for 3,413 captured Confederate soldiers. Hart Island was also leased to the federal government for training and defense purposes during World War II and the Cold War. Following the Civil War, personnel from the U.S. Sanitary Commission were stationed at Bellevue Hospital and helped to establish a morgue for examining and identifying the dead. In 1866, the City Council passed new sanitary codes prohibiting new burial grounds from opening in New York City. The Potter’s Field then in use on Wards Island (established in the 1840s) closed, and City Cemetery on Hart Island (then part of Westchester County) opened in 1869.

In 1872, a highly efficient grid system of burials began on Hart Island that is largely unchanged today. Trenches were laid out in three layers of 50 graves. In 1931, this system changed to sections of two across and three deep with 50 bodies per section. Each pine box is listed as a grave and recorded in ledger books. Consequently, the City’s mortuary service, still operated by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner at Bellevue Hospital, can readily disinter a body for further examination or return it to families claiming the deceased at a later date. In 1931, the City also began recycling graves, which is legal after a body has decomposed to skeletal remains. Due to these practices, City Cemetery is large enough to accommodate New York City’s burial needs indefinitely, making it an important municipal resource.

In 2013, the New York City Council passed legislation requiring the DOC to post its database of burials online and to list its visitation policy. In 2013, a group of eight women working with a charity, The Hart Island Project (HIP), petitioned the City to visit the graves of their infants buried on Hart Island. In 2015, the New York Civil Liberties Union filed a class action lawsuit establishing rights for families to visit graves on Hart Island. Families are now able to visit once a month by appointment. HIP was founded in 1991 to provide public access to information about burials and, in 2014, launched The Traveling Cloud Museum, an online database with an interactive map for locating burial sites and collecting stories of the recently buried. These resources are intended to reconnect Hart Island with communities across the globe.

Hell’s Kitchen, Manhattan

The built environment of Hell’s Kitchen reflects many important aspects of immigrant life at the turn of the century, incorporating the housing, institutions and industrial buildings that provided the livelihoods of newly-arrived New Yorkers for generations. Manhattan Community Board 4 and the office of Council Speaker Corey Johnson have made it a priority to gain landmark protections for portions of the neighborhood in order to preserve its near-pristine historic streetscapes of rowhouses, tenement buildings, religious structures and commercial architecture.

When the western Bronx was annexed by New York City in 1874, it was only a matter of time until this rural area would experience widespread urban expansion and a surge in population. John Mullaly (1835–1915), regarded as the “father of the Bronx Park system,” was a newspaper reporter and editor who looked upon this future growth with concern for the well-being of city residents and for the intelligent development of the city itself. Mullaly’s effort culminated in the 1884 New Parks Act and the City’s 1888-90 purchase of 4000 acres for Claremont, Crotona, Van Cortlandt, Bronx, St. Mary’s, and Pelham Bay Parks, as well as the Mosholu, Bronx, Pelham, and Crotona Parkways that connect the parks to one another. In 1932, 18 years after his death, Mullaly Park in the south Bronx was dedicated in his honor.

To read more click here

Cuando la parte oeste del Bronx se anexó a la ciudad de Nueva York en 1874, fue solo cuestión de tiempo hasta que esta área rural experimentase una urbanización expansiva y una explosión de población. John Murray (1835-1915), considerado como el “padre del sistema de parques de El Bronx,” fue un reportero y editor de periódicos que pensó que este futuro crecimiento sería una amenaza para el bienestar de los residentes y el desarrollo inteligente de la ciudad.

Los esfuerzos de Murray culminaron en 1884 con la Ley de Nuevos Parques, y la compra por parte de la ciudad en 1888-90 de tierras para los parques Claremont, Crotona, Van Cortland, Bronx, St Mary’s, y Pelham Bay, así como también con la creación de las carreteras Moshulu, Bronx, Pelham, y Crotona, las cuales conectan los parques entre sí. En 1931, 18 años después de que Mullay muriera, se le dedicó en su honor el Mullay Park en el sur del Bronx.

Filled with green space, picturesque churches and remarkable historic streetscapes, The Bronx has long been one of New York City’s hidden treasures. In the face of the massive development pressure sweeping across the city, the Historic Districts Council has gathered residents and activists from across The Bronx to create a coalition focused on promoting and preserving historic buildings and neighborhoods throughout the borough. Together, we will be able to better mobilize against inappropriate development and work to protect what makes The Bronx unique.

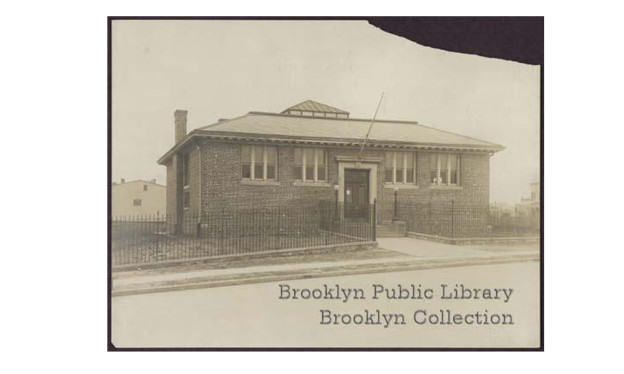

The New York Public Library (NYPL) was formed in 1895 with the consolidation of three private corporations: the Astor Library (founded by John Jacob Astor in 1849), the Lenox Library (founded by James Lenox in 1870) and The Tilden Trust (a fund established in 1886 by Samuel J. Tilden). The NYFCL also joined this consolidation in 1901 in order to benefit from Carnegie’s gift of $5.2 million for 67 library branches to be built between 1901 and 1929 (56 are still standing). Carnegie’s only stipulation was that the city acquire the sites and establish building maintenance plans. To design the buildings, the NYPL organized a committee of architects: Charles F. McKim, Walter Cook and John M. Carrère. In order to stylistically link the branches and save money, the committee decided on a uniform scale, interior layout, character and materials palette for the buildings.

To read more about New York City’s Historic Public Libraries click here

A relative lack of development pressure allowed Staten Island’s small burial grounds to remain. From the 17th century well into the 19th century, family farms occupied much of Staten Island, especially in the south. Within the confines of these farms, “Homestead Graves” or family burial grounds were established. These were some of the first community cemeteries on Staten Island, and many of today’s cemeteries are still named after the families whose homestead burial grounds were sold for public use. Many of the 13 accessible and five inaccessible cemeteries covered in this brochure became abandoned, vandalized or used as dumping grounds in the 20th century.

To learn more about the Historic Staten Island Cemeteries click here

Hunts Point, the Bronx

Much more than massive wholesale markets, this south Bronx neighborhood possesses historic and cultural richness that Dondi Mckellar of Bronx Community Board 2 is working to celebrate and preserve. The 1912 Feldco Building was a center for generations of popular music styles from jazz to salsa to hip-hop, and the area is home to a burial ground for enslaved Africans, vibrant local businesses, architectural gems, and a rich musical and artistic heritage. The group is working to ensure that both long-time residents and newcomers are aware of the neighborhood’s cultural wealth, and that new development is respectful of the area’s architecture and scale.

Inwood is located at the top of Manhattan Island, at the point where the Hudson and Harlem Rivers meet a the Spuyten Duyvil. The area is historically, architecturally and environmentally unique as almost half of the land is public park space that preserves the natural terrain and geological features of the island, as opposed to the designed landscapes of many parks in New York City. In 1906, the extension of the IRT transit lines to Dyckman Street resulted in the rapid development of six- and seven-story apartment houses on land purchased from farms and private estates. Today, Inwood remains characterized by early-20th- century apartment residences built in relation to the preserved landscape of its public parks to the west and south. An industrial area, serving the transportation, sanitation and utility infrastructure of New York City, occupies a large portion of its eastern edge.

To learn more about Inwood click here

Inwood está situado en la parte superior de la isla de Manhattan, en la confluencia del Río Hudson y el Río Harlem, en el barrio Spuyten Duyvil. Esta zona es única en arquitectura, historia y medio ambiente. Casi la mitad del terreno es un parque público que preserva el suelo natural y las características geológicas de la isla, al contrario de los paisajes diseñados en muchos parques en la Ciudad de Nueva York. En 1906, la prolongación de las líneas IRT del subterráneo hacia Dyckman Street, en donde las primeras estaciones de transporte masivo abrieron, resultó en la rápida construcción de casas de apartamentos de seis y siete pisos en terrenos comprados a granjeros y dueños de haciendas privadas. Los inmigrantes de clase trabajadora y de distintos orígenes culturales, buscando mejores condiciones de vida que aquellos edificios estrechos en downtown Manhattan, se mudaron a Inwood para residir en apartamentos nuevos, espaciosos y más asequibles ubicados en construcciones neoclásicas, con estilo italianizante y arquitectura neo-tudor. En la actualidad, Inwood se caracteriza por sus apartamentos residenciales de comienzos del siglo XX, los cuales fueron construidos en concordancia con el paisaje preservado de los parques públicos en el sur y oeste del barrio. Un área industrial, que ofrece infraestructura para las necesidades de transporte, aseo y servicios públicos de la ciudad de Nueva York, ocupa una gran parte del borde oriental.

Jackson Heights is an early-20th-century neighborhood in central Queens, composed of low-rise garden apartments and houses as well as institutional and commercial buildings. It was the first and remains the largest garden-apartment community in the United States— the product of both the early 20th-century model tenement and the Garden City movements.

Jackson Heights was designated as a New York City Historic District in 1993, and an extension of those boundaries, which would meet those of the 1998 National Register Historic District, is currently being sought. This would include buildings that, due to the restrictions placed upon them by the Queensboro Corporation, possess the same quality design, materials and scale of the earliest buildings creating historic Jackson Heights.

To learn more about Jackson Heights click here

Jackson Heights es un vecindario fundado en el comienzo del siglo XX, en el centro de Queens, compuesto de edificios bajos con jardines y casas, junto con edificios institucionales y comerciales. Fue la primera comunidad de apartamentos con jardín, y todavía es la más grande en los Estados Unidos, producto de la corriente de viviendas ejemplares y del movimiento urbanístico Garden City (ciudad jardín) de principios del siglo XX. Hacia finales del siglo XIX, las malas condiciones de vida en los barrios pobres de la ciudad dieron origen a esfuerzos reformatorios para mejorar la vivienda urbana. Como resultado, la luz, la ventilación y el espacio verde abierto se volvieron piezas claves en el diseño de urbanizaciones nuevas. Esto es particularmente evidente en Jackson Heights.

HDC will work with the Kew Gardens Improvement Association and the Kew Gardens Preservation Alliance to help support their campaign to preserve the historic core of the neighborhood, which includes the historic bridge at Lefferts Boulevard, the surrounding historic pre-war buildings, and several blocks of historic houses.

Kingsbridge, the Bronx

This northwestern Bronx community is home to architectural gems from multiple eras and in various styles, from the imposing Kingsbridge Armory to 19th century farmhouses to stunning 1930’s Art-Deco apartment buildings. The Northwest Bronx Community & Clergy Coalition has been working since 1974 with residents and small businesses in the Bronx to prevent displacement, foster equitable economic development, protect housing and maintain strong and stable communities. The NWBCCC is now seeking to identify historic resources in order to better protect and stabilize community character and foster pride in the area’s architecture and history.

With recent landmark designations of Philip Johnson’s AT&T Building (1978), the Citicorp Center (1973-1978), the interior of the UN Plaza’s Ambassador Grill and Lounge (1969-83) and six sites with ties to the LGBTQ community of the 1960’s and 1970’s, the time to assess preserving our recent past has firmly arrived. The Historic Districts Council will work in partnership with Docomomo US and Queens Modern to highlight architecturally and culturally significant buildings of the last 50 years that are unprotected and unrecognized. Beginning with the 1970’s, the decade of HDC’s formation, the partnership seeks to raise public awareness of a time of great change and adversity characterized by a remarkable variety of architectural forms, technical advances and urbanistic ideas. This is the city we’re sending into the future; let’s start talking about the ALL the parts we should keep.

In November 2014, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) announced a plan to clear 95 properties that had been on its calendar for five years or more, but not yet designated as landmarks. The wholesale removal of these properties without considering each one’s merits would have represented a severe blow to the properties and to the city’s landmarks process in general, sending a message that would jeopardize any future effort to designate them.

The Historic Districts Council acted strongly in opposition to this action, and advocated for a more considered, fair and transparent approach. As part of this effort, HDC worked with Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer and a coalition of other preservation organizations to submit an alternative plan for the LPC’s consideration. The plan eventually formed the basis for the LPC’s initiative, entitled “Backlog95,” calling for a series of public discussions to evaluate the properties in geographical groupings.

To learn more about the Landmarks Under Consideration click here

Based in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn, I AM CARIBBEING is dedicated to showcasing Caribbean culture, particularly along the corridors of Flatbush, Church, Nostrand, and Utica Avenues, aka “Little Caribbean.” I AM CARIBBEING is led by Kennya Cummings and Shelley Worrell, two community activists dedicated to highlighting the most culturally iconic places of the area. I AM CARIBBEING is a leading force in this thriving community, where West Indians live, work, and play. HDC will work with I AM CARIBBEING to promote their work commemorating the history of the Caribbean diaspora in New York City.

The westernmost portion of Queens remained predominantly rural and undeveloped until around 1870, when Long Island City was incorporated from the nascent industrial communities of Astoria, Blissville, Hunters Point and Ravenswood. The start of this area’s growth began when the Long Island Rail Road moved its main terminus from Downtown Brooklyn to the East River waterfront in Hunters Point in 1861. In the last quarter of the 19th century, its waterfront became home to oil refineries, lumber yards, factories and chemical plants, while the city’s population tripled from 15,609 in 1875 to 48,272 in 1900. After Queens was consolidated into Greater New York City in 1898, Long Island City’s connections to Manhattan were strengthened with additional transportation options. Banks and manufacturing firms soon gravitated towards Long Island City , which became famous for the large electric signs that dotted the rooftops of its buildings, advertising products like Swingline Staplers, Chiclets and Pepsi Cola to travelers passing through.

To read more about Long Island City click here

Much of the Lower West Side was once underwater, with the Hudson River shoreline running approximately where Greenwich Street is now located. During the colonial period, the settlement at Manhattan’s southern tip was guarded by Fort Amsterdam (renamed Fort George by the British), and later reinforced by the Whitehall Battery. Partially destroyed during the American Revolution, the fort was demolished and the Battery rebuilt as an elegant promenade. The adjacent blocks remained the city’s most elegant residential neighborhood, as evidenced by several surviving Federal-style row houses in the neighborhood. In the lead-up to the War of 1812, the U.S. Government built a new fortification—the West Battery, later renamed Castle Clinton—on an artificial island 300 feet offshore.

By the mid-19th century, fashionable New Yorkers had moved northward and lower Manhattan was given over to commercial activity and tenement housing. Landfill extended the island’s western shoreline, enveloping Castle Clinton, by then repurposed as an immigration station. Horsecar tracks plowed through the neighborhood’s north- south thoroughfares and in 1867 the first elevated train in the country began operating along Greenwich Street. Single-family row houses were split up into multiple units, and purpose-built tenements were erected to cater to the neighborhood’s increasingly diverse immigrant population.

One of the Lower West Side’s most notable immigrant communities was “Little Syria”, which existed along lower Washington Street and the surrounding blocks from the 1880s through the 1920s. The “Great Migration” of Syrians to the U.S. was sparked, in part, by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and the subsequent devastation of the local silk industry. Though government officials often referred to them as “Turks” due to their citizenship within the Ottoman Empire, the community generally identified as Syrian. The majority came from the Mount Lebanon area, and many embraced their Lebanese heritage in the 1920s with the rise of that country’s national independence movement. Most of Little Syria was Christian; approximately half were Syrian Melkite and Lebanese Maronite Catholics.

Manhattan’s Syrian Quarter was central to the lives of other Syrian communities throughout the U.S., both economically and culturally. Its merchants imported—and its factories produced—wares including Oriental rugs, cigarettes and mirrors. Printers modified their machinery to reproduce Arabic characters, and more than 50 Arabic newspapers and periodicals were produced at its height.

The Lower West Side’s Syrian community began to decline in numbers and visibility during the 1920s, the same period in which the neighborhood was experiencing profound changes to its built environment. The Immigration Act of 1924 halted new arrivals to sustain the neighborhood, and residents either moved or Syrian quarters or assimilated into the general population. Rising property values also played a part as the commercial development of the Financial District increased during the Roaring Twenties. By the 1930s much of the neighborhood’s low-scale row houses and tenements had been replaced by Art Deco skyscrapers. Today the neighborhood has largely vanished, although several significant sites remain nestled among the office towers of Lower Manhattan.

Unlike other parts of Midtown, one can still experience the full flavor of this neighborhood’s evolution from a residential enclave into an entertainment district anchored by Madison Square Garden, and later to one of the nation’s most important mercantile centers before WWI. At this time, only a small portion of this area west and north of Madison Square is protected as a historic district.

To read more about the Madison Square North click here

HDC will partner with LANDMARK WEST! to explore Manhattan Avenue (West 100 to 104th Streets) on the Upper West Side. HDC will help LW! research the area’s social and architectural history, engage with NYCHA residents about their historic campuses, and advocate for increased protection at the local and national levels.

Morningside Heights posee la mayor concentración de edificios institucionales construidos en un periodo de tiempo relativamente corto a comienzos del siglo XX, tanto en la ciudad como en cualquier otra parte de Estados Unidos. Es el hogar de sitios monumentales de oración, educación superior y sanación, los cuales acentúan el fondo de casas en hilera y construcciones de apartamentos que culminan en un elegante paisaje urbano elegante y agradable a la vista. Topográficamente, Morningside Heights está situado en un altiplano históricamente conocido como Harlem Heights, mientras que geográficamente está rodeado de West 110th Street al sur, West 125th Street al norte, Morningside Park al este y Riverside Park al oeste, dos parques diseñados por Frederick Law Olmsted.

Morningside Heights is graced with the highest concentration of institutional complexes built in a relatively short period at the turn of the 20th century, both in the city and anywhere in the United States. It is home to monumental places of worship, higher learning and healing, which accentuate its backdrop of rowhouses and apartment buildings, culminating in streetscapes that are both elegant and eye-filling. Topographically, it is situated on a plateau historically known as Harlem Heights, while geographically it is bounded by West 110th Street to the south, West 125th Street to the north, and two Frederick Law Olmsted–designed parks to the east (Morningside Park) and to the west (Riverside Park).

Morningside Heights was calendared by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in September 2016 and had a public hearing on December 6, 2016.

To learn more about Morningside Heights click here

HDC will support Friends of Mosholu Parkland work to create a Master Plan for Mosholu Parkway to improve the quality of life for the local communities, including Bedford Park and Norwood. We will also assist in their preservation efforts for sites including The Bronx Victory Memorial and Frank Frisch Field.

El Bronx fue nombrado en honor a Jonas Bronck, un inmigrante europeo nórdico, quien llegó a la colonia de Nueva Holanda en 1639. Bronck y su esposa Teuntje Joriaens crearon una granja en lo que ahora se conoce como Mott Haven, en la intersección del Río Harlem y Bronx Kill, con vistas a la isla Randall. En 1670, gran parte del área fue adquirida por la familia Morris, quienes construyeron una casa de campo llamada Morissania. La familia mantuvo su propiedad, y el área estuvo escasamente poblada hasta inicios del siglo XIX. La llegada del ferrocarril de Nueva York y Harlem, anunciada en 1840, convenció a la familia Morris de aceptar proyectos suburbanos en su hacienda.

Jordan L. Mott, homónimo del barrio Mott Haven, compró unas grandes extensiones de tierra de la familia Morris en 1841 y 1848. Con la intención de crear una “zona céntrica del Condado de Westchester” (de la cual Mott Haven todavía era parte) Morris dispuso calles y lotes para construcciones, y empezó a promocionar este lugar como Mott Haven. De acuerdo con sus planes, la parte sur tendría uso industrial, con su propia carpintería metálica, y comunicado con un canal de 3000 pies, construido específicamente para este fin. La parte norte fue reservada específicamente para edificios residenciales prolijos, protegidos por cláusulas que restringían elementos “dañinos para la salud o nocivos u ofensivos para el barrio”. Otros constructores pronto siguieron los pasos de Mott en el sur de El Bronx, comprando grandes extensiones de tierra de la familia Morris, y diseñando sus propios suburbios, como Wilton (subdividido en 1857) y Nueva York del Norte (1860), ambos parte de Mott Haven en la actualidad. La familia Morris también formó parte del auge de las construcciones, y fueron quienes planearon el barrio industrial Port Morris.