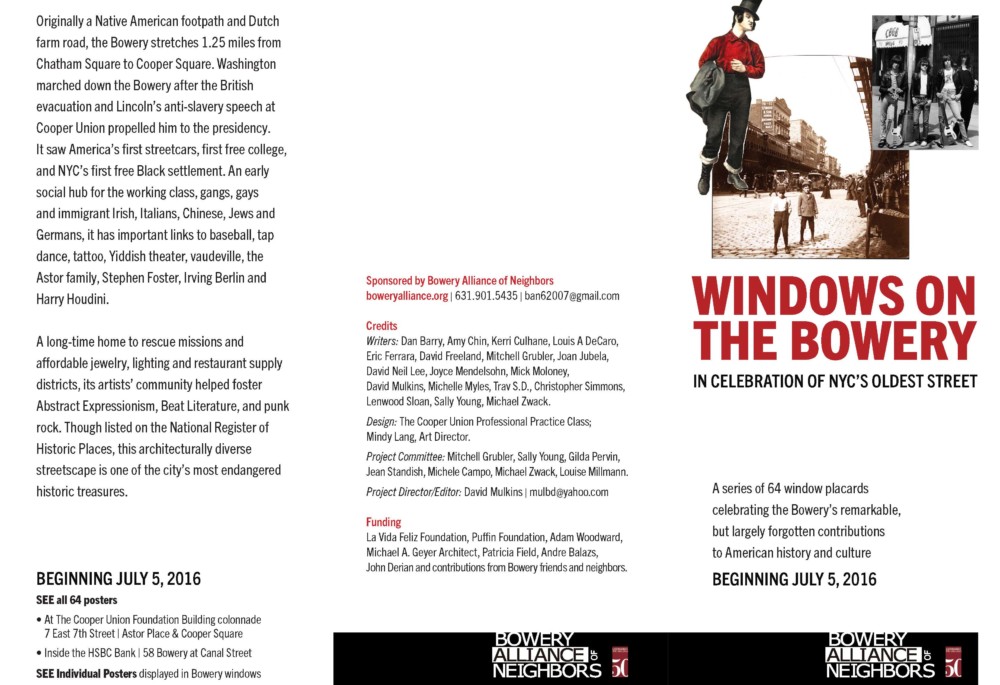

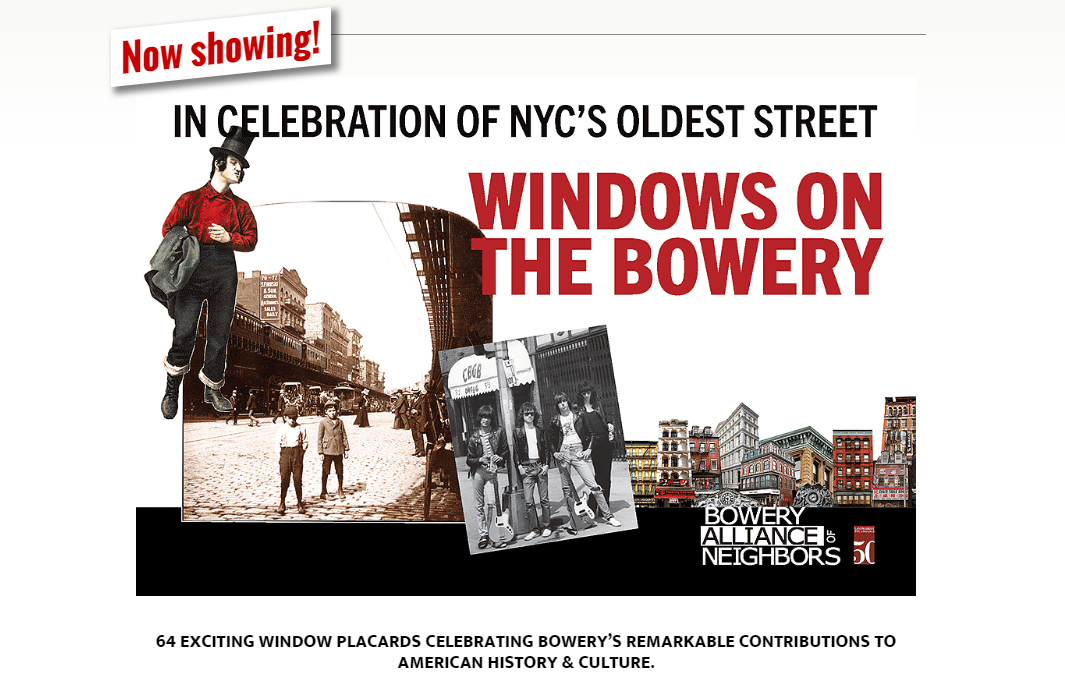

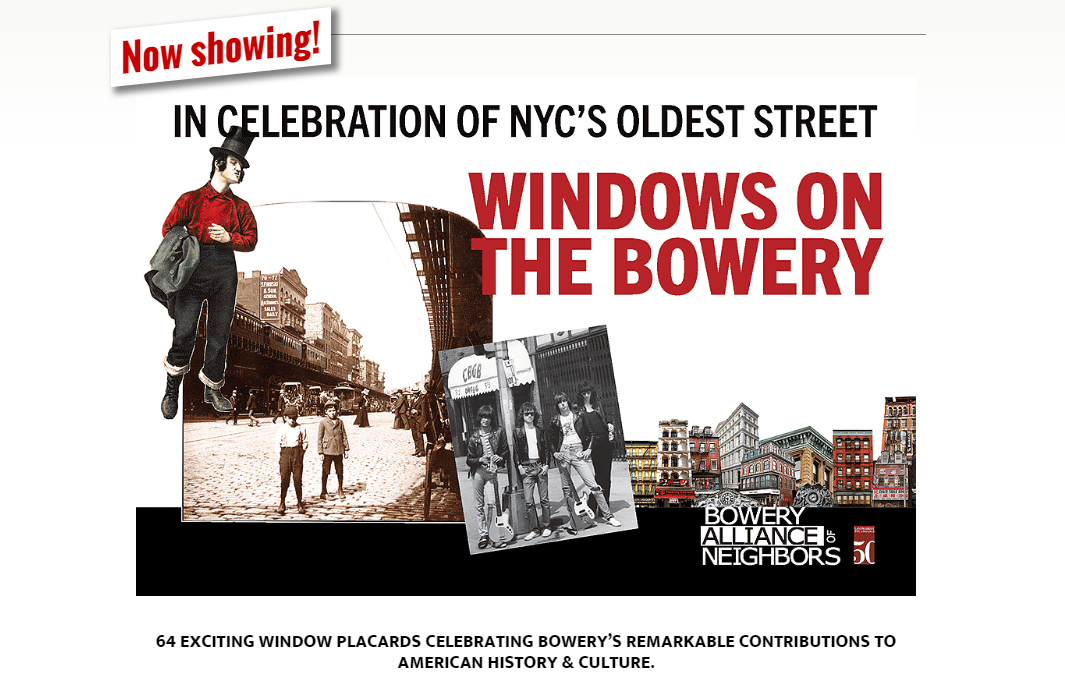

Originally a Native American footpath and Dutch farm road, the Bowery stretches 1.25 miles from Chatham Square to Cooper Square. Washington marched down the Bowery after the British evacuation and Lincoln’s anti-slavery speech at Cooper Union propelled him to the presidency. It saw America’s first streetcars, first free college, and NYC’s first free Black settlement. An early social hub for the working class, gangs, gays and immigrant Irish, Italians, Chinese, Jews and Germans, it has important links to baseball, tap dance, tattoo, Yiddish theater, vaudeville, the Astor family, Stephen Foster, Irving Berlin and Harry Houdini.

Originally a Native American footpath and Dutch farm road, the Bowery stretches 1.25 miles from Chatham Square to Cooper Square. Washington marched down the Bowery after the British evacuation and Lincoln’s anti-slavery speech at Cooper Union propelled him to the presidency. It saw America’s first streetcars, first free college, and NYC’s first free Black settlement. An early social hub for the working class, gangs, gays and immigrant Irish, Italians, Chinese, Jews and Germans, it has important links to baseball, tap dance, tattoo, Yiddish theater, vaudeville, the Astor family, Stephen Foster, Irving Berlin and Harry Houdini.

A long-time home to rescue missions and affordable jewelry, lighting and restaurant supply districts, its artists’ community helped foster Abstract Expressionism, Beat Literature, and punk rock. Though listed on the National Register of Historic Places, this architecturally diverse streetscape is one of the city’s most endangered historic treasures.

The Bowery is one of New York’s most storied streets with a rich and varied past that reflects the hurly-burly history of New York City itself. As Manhattan’s oldest thoroughfare, the Bowery began as a Native American trail and originally extended the length of the island north to south. New York’s early Dutch settlers widened the trail for their own use to connect New Amsterdam at the tip of Manhattan with their farms, or bouweriesfarther north. This “Bouwerie Lane” became simply “Bowery Lane” under the English in 1813 and the name has remained unchanged since.

The Bowery remains an architecturally rich area with a unique mix of Federal-style rowhouses, grand institutional buildings, tenements and commercial loft buildings, each type speaking to a different era in the boulevard’s storied history. Many of these buildings were spared because the elevated rail line, which was removed in the 1950s, deterred speculative development for decades. In recent years, however, new large-scale development has increased and is putting the built heritage of the Bowery greatly at risk.

To learn more about the Bowery click here

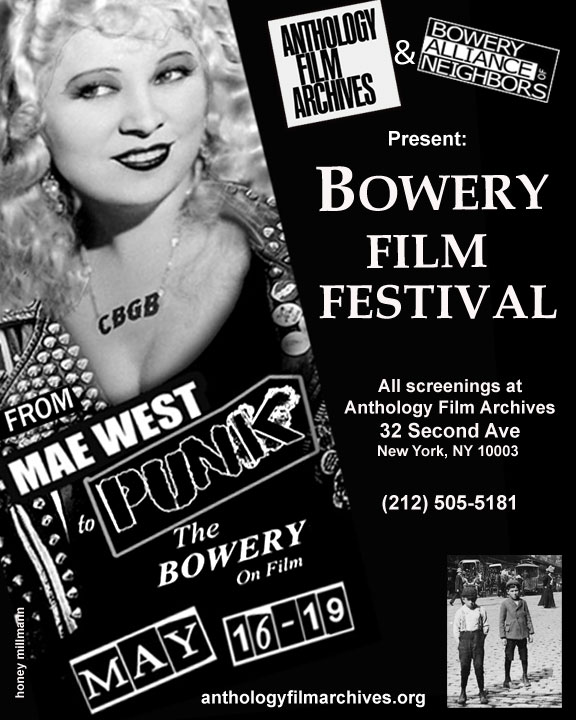

The Bowery on film dates to the earliest days of cinema, when its rowdy, amoral reputation provided titillating material for early peep shows, one-reelers, and silent era features like Raoul Walsh’s REGENERATION (1915). It figured even more prominently in the early sound era when Boweryesque song and slang were exploited to the full in films like SHE DONE HIM WRONG (1933) with Mae West. The ravaged lives of the Bowery’s skid row have long fascinated artists, as seen in the documentary classic ON THE BOWERY (1956). Scott Elliott’s SLUMMING IT gives a wonderful overview of Bowery history, and Mandy Stein’s BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE is a poignant appreciation of Hilly Kristal’s legendary CBGB, made during the club’s final days.

With the Bowery imperiled by developers at every turn, we end the series with THE VANISHING CITY, a powerful look at the forces that threaten to obliterate the character and culture of our communities.

For more information about this film series click here

Presented by: Bowery Alliance of Neighbors

www.boweryalliance.org

May 8, 2014

Sponsored by Lower East Side Preservation Initiative

Neon signage – bold, colorful, flashy, and often beautiful – is emblematic of New York itself, and particularly the Lower East Side with its exuberant and diverse immigration, political, and cultural history.

Join Tom Rinaldi, architectural designer and author of New York Neon, in a rollicking tour of some of the most striking and historically interesting Lower East Side neon, including Katz’s, Russ and Daughter’s, Gringer Appliances, and lesser known gems.

Thursday, May 8th, 6:30 PM

Meet in front of John’s Restaurant 302 East 12th St. just west of 2nd Ave.

Admission: $20 LESPI Members: $15

Reservations are limited: advance ticket purchase recommended

Purchase tickets at www.NYCharities.org

Contact Richard:347-827-1846 or info@LESPI-nyc.org

You can purchase New York Neon here

357 Bowery;

Carl Pfeiffer;

1870|

This building is another vestige of the once large German population in the Bowery area. It is also reflective of the necessity for fire insurance in the 1870s, when fires were common and a major problem in dense urban areas like New York. This building is a smaller-scale example of insurance-company building styles of the 1870s, the design of this building having been inspired by more prominent insurance-company buildings. It was fashionable during this time, especially for insurance buildings, to possess mansard roofs, dormers, cast-iron storefronts and high basements, as this building has. The building today is completely residential and is a New York City landmark.

Julius Rockwell & Son;

1899|

This four-story brick building was a cigar factory from 1899 until 1926, when it became Holy Name Mission. The mission served the homeless until 1962. In 1964 it became the Amato Opera and saw 61 seasons before it closed and went up for sale in 2009.

F. W. Klemt;

1883|

Originally only three stories, this building gained an additional three stories in the 1880s by H. Bruns, the owner of the building. He incorporated his initials as decorative elements that can still be seen on the second story and on the fire escape. It was a lodging house in the 1880s and continues to lodge men today, as it is home to the Bowery Residents’ Committee.

J. and D. Jardine;

1871|

This five-story Italianate building is unusual and stands out on the Bowery because of its yellow color. The yellow façade is clad in Dorchester stone, a sandstone from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, Canada, that was especially popular in the 1870s and 1880s. This building retains many original features, such as its window hoods, brackets, cornice and ironwork. The building was used as a dwelling and store until the early 1880s, when it became the Great Northern Hotel and later the Windsor Lodging House, which was notorious for thieves.

227 Bowery;

William Jose, Marshal L. and Henry C.;

Emery, Diffendale and Kubec;

1876; alterations 1908–1909; renovations 2001|

The Bowery Mission was organized in 1879 and at the time was the third rescue mission in America. It was organized as a response to the rampant homelessness on the Bowery after the Civil War. The mission moved to the five story building (which originally was a coffin factory) in 1909, and President William Taft visited later that year. After 1909 this building received upgrades including fireproofing, and it also received a new chapel and façade. The Tudor Revival style was chosen because it is emulative of an English inn, suggesting a welcoming public place. The stained-glass windows depict the parable of the Prodigal Son and are attributed to Tiffany-trained artist Benjamin Sellers. The three-story building next to the mission is a circa 1830 Federal-style house. It was modified in 1895 to the Italianate style it retains today and was unified with the mission next door in 1980.

222 Bowery;

Bradford L. Gilbert;

1884–1885|

This was the first YMCA to open in New York City and originally was called the Young Men’s Institute. It was built to provide young men with shelter and physical and social enrichment as an alternative to the overcrowded flophouse accommodations that dominated the Bowery. It remained a YMCA until 1932, when it was converted to lofts/residential space subsequently inhabited by many world-renowned artists. It is not common for an institutional building to be designed in the Queen Anne style—a style usually reserved for domestic architecture. This building has been a New York City landmark since 1998.

Originally a Native American footpath and Dutch farm road, the Bowery stretches 1.25 miles from Chatham Square to Cooper Square. Washington marched down the Bowery after the British evacuation and Lincoln’s anti-slavery speech at Cooper Union propelled him to the presidency. It saw America’s first streetcars, first free college, and NYC’s first free Black settlement. An early social hub for the working class, gangs, gays and immigrant Irish, Italians, Chinese, Jews and Germans, it has important links to baseball, tap dance, tattoo, Yiddish theater, vaudeville, the Astor family, Stephen Foster, Irving Berlin and Harry Houdini.

Originally a Native American footpath and Dutch farm road, the Bowery stretches 1.25 miles from Chatham Square to Cooper Square. Washington marched down the Bowery after the British evacuation and Lincoln’s anti-slavery speech at Cooper Union propelled him to the presidency. It saw America’s first streetcars, first free college, and NYC’s first free Black settlement. An early social hub for the working class, gangs, gays and immigrant Irish, Italians, Chinese, Jews and Germans, it has important links to baseball, tap dance, tattoo, Yiddish theater, vaudeville, the Astor family, Stephen Foster, Irving Berlin and Harry Houdini.