230-236 East 90th Street

Thomas H. Poole

1886-87

The rapid development of Yorkville following the arrival of elevated trains can be traced directly through the construction of Catholic churches in the area. These included St. Monica’s (founded 1879), St. Jean Baptiste (1882), St. Joseph’s (1888), St. Elizabeth of Hungary (1891) and St. Stephen of Hungary (1902). The Church of Our Lady of Good Counsel was one of the grandest, occupying an imposing building clad with Vermont marble. The design was called “thirteenth century English Gothic” by The New York Times and features crenellations and polygonal turrets. The heaviness of the rough-faced upper story is relieved by a giant stained glass window with delicate Gothic tracery, and the refined lower stories are clad in smooth ashlar stonework. The adjacent rectory was designed at the same time by Thomas H. Poole, a congregant who designed several Catholic churches in New York City. If you need a place to rest and reflect at the end of your tour, Ruppert Park (named after the brewery that once stretched from East 90th to 94th Streets) is located across the street.

1716-1720 Second Avenue

Lamb & Rich

1886-87

This pair of stately Romanesque Revival style brick apartment buildings was constructed at a time when apartment-style living was becoming more socially acceptable for New York’s burgeoning middle class. They exemplified the use of distinctive architecture and evocative naming (similar to today’s “branding”) to elevate the image of the multiple-dwelling building type, which had long been associated with the cramped and squalid quarters of Manhattan’s worst tenement-house districts. In this case, the choice of the noble-sounding names “Kaiser” and “Rhine” signaled the overwhelmingly German heritage of the buildings’ presumed occupants (the U.S. Census for 1900 shows that most of the residents were of German descent), as well as the prominent Rhinelander family’s involvement in their construction and in real estate development in Yorkville in general. Although built as two separate structures joined along a party wall with interior courtyards, the buildings’ Second Avenue façades present a unified, monumental appearance. The decorative iron balcony and pent eave roof anchor the façade’s center bay, while the round arches that are a hallmark of the Romanesque Revival style play across the façade at different scales. The red-orange brick façade is embellished by rich geometric patterning and delicate Romanesque Revival style detailing, including corbels, quoins and window spandrels featuring delicate cartouches with ribbons. The building was recently restored with the removal of the white paint that had been obscuring the building’s subtle texture and fine ornament. With luck, the cornices that flanked the pent eave roof in this once-picturesque roofline will also be restored.

316 East 88th Street

Barney & Chapman

1896-97

NYC Individual Landmark, National Register of Historic Places

The Church of the Holy Trinity complex—including church, parish house and parsonage—was sponsored by Serena Rhinelander in memory of her father (William C. Rhinelander) and grandfather (William Rhinelander). The property was once part of William Rhinelander’s 72-acre farm. The parish was established when the neighborhood church and mission of St. James joined with Holy Trinity Church, formerly of Midtown. Completed in 1897, this complex is an outstanding example of Gothic Revival architecture, clad in golden-hued Roman brick and terra cotta with a brownstone-like color and texture. The buildings’ impressive towers, turrets, chimney stacks and spires evoke a French Renaissance style château. St. Christopher’s House was the first building completed, and served neighborhood youth as a clubhouse, recreation center and kindergarten. The architects Barney & Chapman had earlier designed the French Gothic-inspired Grace Mission complex that still stands at 14th Street and First Avenue for Serena’s nephew; though more modest in scale than Holy Trinity, it was a clear precedent. If Holy Trinity is open, it is well worth a look inside.

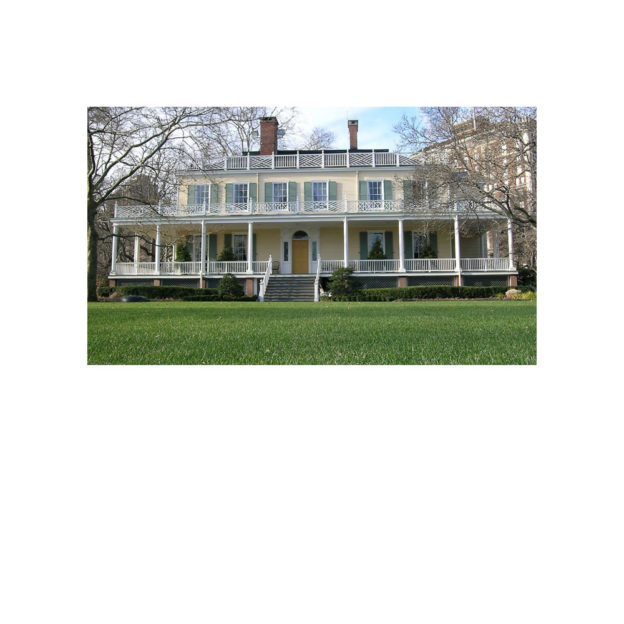

East 88th Street and East End Avenue

Ezra Weeks

1799-1804

NYC Individual Landmark, National Register of Historic Places

Most New Yorkers know Gracie Mansion as the home of New York City’s mayors, and indeed it has served as the official abode since 1942, when Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia first took up residence there. The stately Federal-style mansion was originally built as the country estate of merchant Archibald Gracie, who in 1798 purchased the land from British loyalists. The site’s naturally high topography offered strategic advantages, and by the 1770s Gracie Point—as it was then called—was the scene of military activity and fortifications. Over the centuries since then, Gracie Mansion has been many things: country seat, first home of the Museum of the City of New York and ice cream parlor. The elegant frame building with its wide porch now sits quietly within the picturesque landscape of Carl Schurz Park, overlooking the East River, and is maintained by the New York City Parks Department. It was also among the first New York City Landmarks, designated in 1966. The only mayor not to have lived at Gracie Mansion full time was Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who felt that the house should be fully open to the public (and that mayors should pay for their own housing).

photo credit nyc.gov

NYC Historic District, National Register of Historic Places

The Henderson Place Historic District is an early example of a planned real estate development intended to cater to “persons of moderate means.” In 1880-82, John C. Henderson, a fur and straw goods merchant, planned for 32 modestly-sized rowhouses on the north side of East 86th Street, both sides of Henderson Place (the short alley running north from the east end of 86th Street), the west side of East End Avenue (then known as Avenue B) and the south side of East 87th Street. The eight houses built on the west side of Henderson Place were demolished sometime after 1940 and replaced with a high-rise building. Because the houses of Henderson Place were smaller than the average four- or five-story brownstone—only 18 feet wide and three stories high—they rented for slightly less than the going rate of $700 to $1,500 a year for an entire rowhouse. Despite Henderson’s choice of the prestigious firm of Lamb & Rich, who also designed The Kaiser & The Rhine apartment buildings (site 19), to design the picturesque Queen Anne-style rows, Henderson Place was not generally regarded as a desirable address until the 1920s. By that time, a Duke and Duchess could be found living at 140 East End Avenue, the corner building anchoring the southern end of the development.

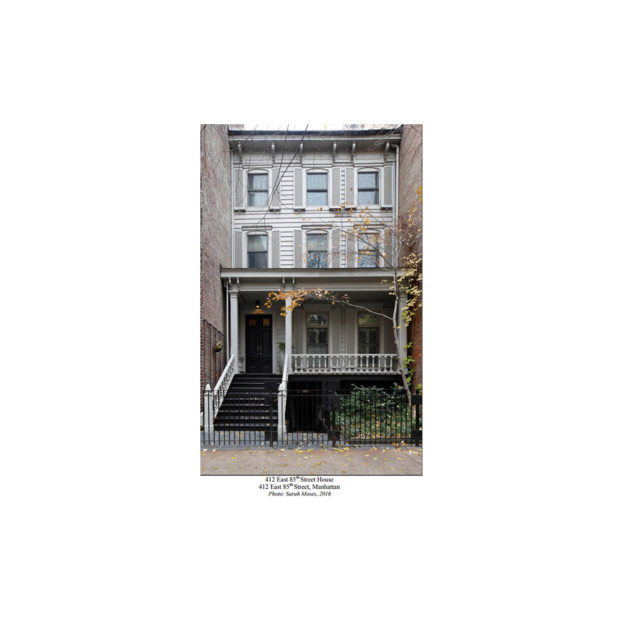

c. 1861

NYC Individual Landmark

412 East 85th Street is a rare surviving example of a wood-frame building in Upper Manhattan. Built by an anonymous craftsman, the house is one of only six wood-frame buildings still standing in this section of the city. Because of the very real danger of fire in urban settings, during the 19th century the construction of wood buildings was increasingly prohibited in dense sections of New York. In 1866, Manhattan’s “fire limit” was extended north to 86th Street, leaving 412 East 85th Street among the last wood buildings to be constructed on the Upper East Side. The house is a modestly-sized three-story structure, set back from the sidewalk and overshadowed by the taller 20th century apartment buildings book-ending this block. The building expresses a simplified Italianate style, featuring a raised brick basement, a three-bay façade clad in clapboard siding, a porch with a tall stoop, floor-length parlor windows and a prominent bracketed cornice. Originally occupied as a single-family residence, by the turn of 20th century the building had been converted for multi-family use and the raised basement was converted to commercial use—both reflections of Yorkville’s changing demographics. Over the decades since the 1950s, the heavily altered house has been restored in phases, resulting in its present appearance.

*Photo courtesy Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts

339-341 East 84th Street

Michael J. Fitz Mahoney

1888-89

National Register

Over its history, this church has been associated with three German congregations, including one of New York City’s earliest. The inscription above the main entrance still announces (in German) the German Evangelical Lutheran Church of Yorkville, which originally commissioned the building. A smaller inscription beside the left entrance lists two dates: 1883, the year that congregation was founded; and 1888, the year the cornerstone was laid. The building, though relatively austere on the interior, proved too costly for the Evangelical congregation to maintain. In 1892, it was sold at auction and the Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church moved in. A half century later, in 1946, Zion merged with St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. The latter congregation was established around 1847 as a branch of the even older St. Matthew’s, and its original house of worship at 323 East 6th Street still survives. In 1904, St. Mark’s was devastated by the General Slocum tragedy, in which roughly 1,000 people died when an excursion boat caught fire in the East River. The disaster led many Germans to abandon Kleindeutschland, with many moving to Yorkville. St. Mark’s persevered for a number of decades, but it too eventually moved northward, bringing its altar, which still adorns the interior.

244 East 86th Street

Charles W. Clinton

1879-80

The six-story Manhattan is one of many middle-class residential buildings developed by the Rhinelander Estate in Yorkville beginning in the 1870s. It is notable as an early example of “French Flats,” a building type that was a cut above a tenement or boarding house, with private bathrooms and windows in every room, but lacked the amenities of high-class apartment houses or hotels, which had servants’ quarters or fancy common dining rooms. French Flats evolved in the 1870s as demand grew for affordable, socially respectable working- and middle-class housing, and many of the earliest examples were built on the Upper East Side. Architect Charles Clinton contiguously designed the Seventh Regiment (Park Avenue) Armory, and there is certainly an architectural kinship between this relatively humble five-story building and the monumental and imposing armory. Both buildings feature monolithic red brick façades enlivened by contrasting stone banding and capped by muscular corbelled brick cornices. The Manhattan was built around an interior courtyard and made use of two airshafts to ensure sufficient light and ventilation in every apartment. The Rhinelanders managed the building until 1961, when they sold the property. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission has called the Manhattan one of the last surviving large apartment houses of this era anywhere in the city.

1491 Third Avenue

George Dress

1930

This unusual Art Deco music hall is distinguished by its wonderful terra-cotta ornament, which hints at the building’s original use with musical lyre motifs in the spandrels between the second- and third-story windows. According to city permits, the ground floor originally contained stores and a cabaret, the second and fourth stories offices, and the third floor a “hall for public assembly.” One of its earliest tenants was the Mayo Ballrooms (named after the Irish county), which advertised itself as “New York’s Most Beautiful Irish-American Ballroom.” (Its interior was divided into Irish and American sections by a folding partition that would be thrown open at the end of the evening to let everyone mingle and enjoy each other’s music.) The building was commissioned by Peter Doelger, Inc., a real estate company that evolved from one of New York’s older German brewing operations. A few doors up, in front of 1501 Third Avenue, is one of New York’s landmark street clocks, manufactured by the E. Howard Clock Company and designed to resemble a giant pocket watch, likely an advertisement for the pawnbroker who occupied the adjacent storefront.

305-311 East 82nd Street

C. B. J. Snyder

1904

When P.S. 290 (originally P.S. 190) opened, it had the capacity to serve 1,600 students. Architect C. B. J. Snyder was Superintendent of School Buildings from 1891 to 1923 and was instrumental in modernizing the city’s school buildings through new technologies, such as passive venting, and the implementation of standards for fireproofing and safety, as well as classroom, corridor and stair design. P.S. 290 was part of a citywide school construction campaign to address the city’s critical shortage of school facilities. By the turn of the 20th century, both rising immigration rates and the Compulsory Education Law of 1894, which mandated school attendance until the age of 14, meant that overburdened public schools were literally turning children away at the door. During his long tenure, Snyder oversaw the construction of around 200 new school buildings and countless renovations to existing schools. Not only was he concerned with the functionality of the buildings and the comfort of the students, Snyder clearly thought of public schools as important contributions to civic architecture. P.S. 290 is designed in a robust Beaux-Arts style, using a bold palette of rusticated red and buff brick and chunky limestone ornament, like the lion’s head at the main entrance. Today, the building is home to the Manhattan New School, a magnet school specializing in literacy instruction. Note the separate ‘Boys’ and ‘Girls’ entrances that can still be seen at either end of the building.