The New York Public Library (NYPL) was formed in 1895 with the consolidation of three private corporations: the Astor Library (founded by John Jacob Astor in 1849), the Lenox Library (founded by James Lenox in 1870) and The Tilden Trust (a fund established in 1886 by Samuel J. Tilden). The NYFCL also joined this consolidation in 1901 in order to benefit from Carnegie’s gift of $5.2 million for 67 library branches to be built between 1901 and 1929 (56 are still standing). Carnegie’s only stipulation was that the city acquire the sites and establish building maintenance plans. To design the buildings, the NYPL organized a committee of architects: Charles F. McKim, Walter Cook and John M. Carrère. In order to stylistically link the branches and save money, the committee decided on a uniform scale, interior layout, character and materials palette for the buildings.

To read more about New York City’s Historic Public Libraries click here

121-23 14th Avenue;

Heins & La Farge, 1904;

NYC IL|

The only Carnegie-funded library to be designed by the noted firm of Heins & La Farge, this building resembles those contemporaneously designed by the firm for the Bronx Zoo’s Astor Court. The firm was also responsible for a number of the city’s subway stations and for early designs of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. The citizens of College Point donated the land for the library and the books were donated by the Poppenhusen Institute, founded in 1868 by German-American businessman Conrad Poppenhusen as a kindergarten and community center. The stipulation of the institute’s gift was that the library would bear its name. The Classical Revival style library is clad in yellow Roman brick with limestone trim, and features a projecting entrance bay with stone banding and a broken pediment above the arched doorway, an ornate cornice with stone shells and two stone cartouches with reliefs of open books. A rear addition was constructed in 1937. The Poppenhusen Branch was designated a New York City Individual Landmark in 2000

35-51 81st Street;

S. Keller, 1949-52;

NYC HD|

A relative latecomer amongst the early 20th century garden apartment buildings and homes that characterize the Jackson Heights Historic District, the Jackson Heights Branch was constructed just after World War II. The building is an excellent example of the International Style with its simple, asymmetrical and unornamented facade. The cast stone and glass building with a flat roof occupies a large midblock site. The box-shaped entryway includes a recessed bay made up of three glass and aluminum doors with transoms and windows rising to the second floor. On either side of the entrance bay are two vertical rows of small square window openings, which provide some of the only ornament on the façade. Above the entrance, the raised metal letters and numbers identifying the library still retain their mid-century typeface. The Jackson Heights branch is located in the Jackson Heights Historic District.

41-17 Main Street;

Polshek Partnership, 1998|

The Flushing Branch of the QBPL was Queens’ first public library. Established as the Flushing Library Association in 1858 and open to members as a subscription library, it became a free circulating library in 1869. In 1906, a Carnegie-funded structure designed by Lord & Hewlett in the Georgian Revival style replaced the wood frame building on this site. The Carnegie building was demolished in the mid-1950s and replaced with a Modern style building, completed in 1957. In 1993, that building was demolished to make way for the branch’s latest phase, a sweeping glass and steel structure completed in 1998.

89-11 Merrick Boulevard;

Kiff, Colean, Voss & Souder, the Office of York & Sawyer, 1966;

renovation: Gensler, 2013;

Children’s Library Discovery Center: 1100 Architect and Lee H. Skolnick Architecture and Design Partnership,; 2011|

In the early 1960s, when an expansion of the four-story, Georgian Revival style Central Library at 89-14 Parsons Boulevard was deemed necessary, an entirely new building was planned instead. The old building, completed in 1931, was repurposed as a courthouse, and has since been replaced by a large apartment building. Located six blocks to the east, the new Central Library was lauded for its functional and streamlined approach to book circulation, with supermarket-like checkout counters and conveyor belts and electric dumbwaiters for book returns. The library includes a large collection on the history of Queens and Long Island. Its simple exterior features two wall-mounted reliefs by sculptor Milton Hebald. In 2011, the Children’s Library Discovery Center wing was added on 90th Avenue, and in 2013, renovations to the main building, including glass at the recessed entryway, were completed.

61 Glenmore Avenue Lord & Hewlett, 1908;

581 Mother Gaston Boulevard William B. Tubby, 1914;

NYC IL|

The simple, free-standing Brownsville Branch, today flanked by high-rise public housing, was once bounded by single-family residences. Before it opened, the neighborhood was growing so dramatically that the building had to be enlarged before it was completed. Due to overwhelming demand by local children, another site just six blocks to the south was purchased at Stone (now Mother Gaston Boulevard) and Dumont Avenues for the Brownsville Children’s Library. Stylistically divergent from the other Carnegie libraries, the Brownsville Children’s Library was designed in the Jacobethan style, rendering it a sort of hybrid between library and fairytale castle. It is said to be one of the world’s first public libraries devoted to children. The exterior features stone carvings depicting characters and scenes from children’s literature, while the interior embraces a child-appropriate scale and features beloved details, like rabbits carved into the wooden benches. After World War II, the library opened to all age groups, renaming itself the Stone Avenue Branch. The Stone Avenue branch was designated a New York City Individual Landmark in April 2015.

431 Sixth Avenue;

Raymond F. Almirall, 1905-06;

NYC IL|

This library was originally the Prospect Branch, housed beginning in 1900 in Prospect Park’s Litchfield Villa and consisting solely of books related to natural history. As Park Slope’s population grew, the demand for a larger, all-purpose library led to its relocation in 1901 to several storefronts on 9th Street between 5th and 6th Avenues. By 1904, the city purchased a large site and began planning for a new Carnegie-funded building. Its name was changed to Park Slope in 1975. The Classical Revival style, brick-clad building with limestone trim features an imposing, projecting portico entrance with Doric columns and a stone pediment. Like those found on the Pacific Branch, the torches in the keystones above the entrance and windows represent the light of learning. Its intact interior features stained glass, tiled fireplaces, wood paneling and marble mosaic floors. The Park Slope branch was designated in 1998.

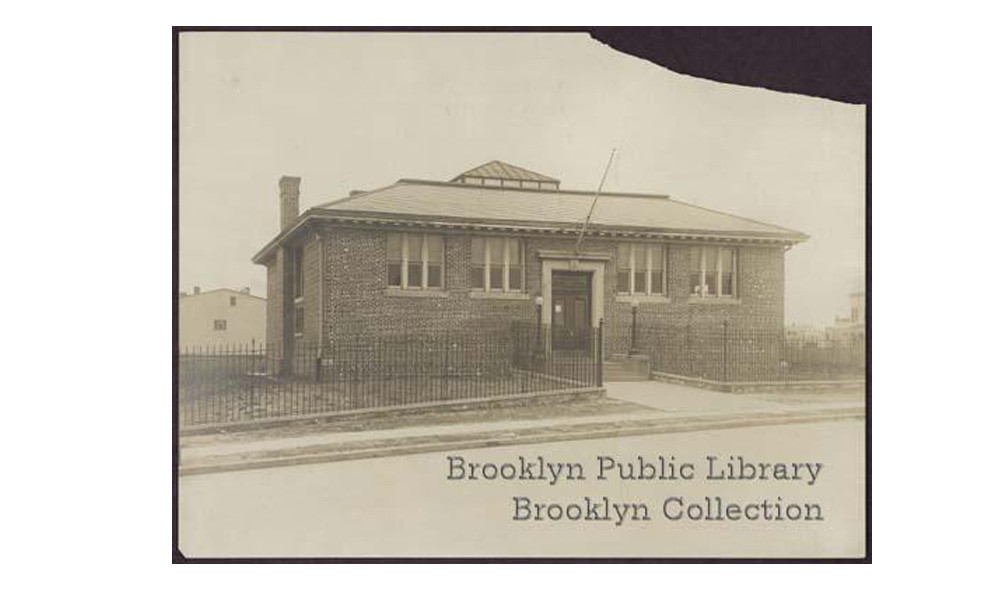

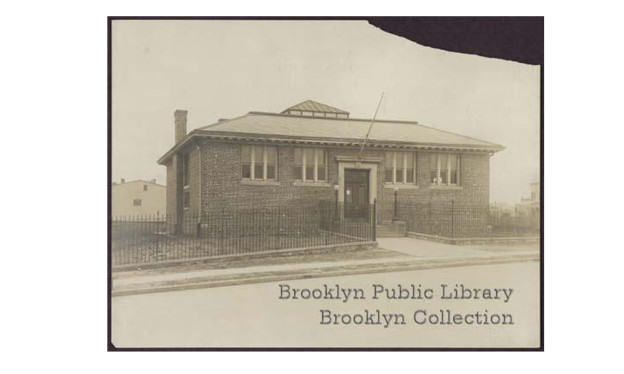

25 Fourth Avenue;

Raymond F. Almirall, 1903|

Brooklyn’s first Carnegie library, the Pacific Branch (named for its location at Pacific Street) was heralded upon completion for its dignified Beaux Arts design. The interior of the building, which has retained its original two-story stacks, was also praised for its light, air and efficient use of space. The building’s brick façades feature prominent limestone trim, including keystones above the arched door and window openings and oversized torches and swags supporting the cornice. The building has had a difficult history, including early damage in 1914 during the construction of the nearby subway, as well as a number of fires. Murals completed in 1939 by the Works Progress Administration graced the second floor for a number of years, but are no longer extant. Despite widespread support, the branch is not a designated city landmark. In 2013, it was under threat of being sold to a developer, but public outcry and political pressure led the BPL to reconsider these plans.

Grand Army Plaza at Flatbush Avenue and Eastern Parkway;

Alfred Morton Githens & Francis Keally, 1941;

sculptural elements: Thomas Hudson Jones and C. Paul Jennewein;

NYC IL, NR-P|

The original 1907 design for the BPL’s Central Building was the work of Raymond F. Almirall, the architect of the Pacific, Park Slope, Bushwick and Eastern Parkway Branches. The grand Beaux Arts design, inspired by contemporary libraries in Europe, with a domed roof and colonnaded entrance, was meant to fit in stylistically with the nearby Brooklyn Museum and Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Arch. Though construction began in 1911, the project was beset with political and financial troubles and stalled in 1929. In 1935, architects Alfred Morton Githens and Francis Keally were commissioned to redesign the building, incorporating the completed foundations and steel structure. The resulting Modern Classical, limestone-clad building features a concave front façade with a 50-foot-tall entrance portico and striking sculpted Art Deco ornamentation. It is one of Brooklyn’s most well-known and frequently used public buildings. The Central Building was designated a New York City Individual Landmark in 1997 and is listed on the State and National Register of Historic Places.

7448 Brighton Street;

Carrère & Hastings, 1904;

NYC IL|

In 1899, the Tottenville Library Association established the Tottenville Free Library, Staten Island’s first free public library with a dedicated space and professional staff. In 1903, the association merged with the NYPL and its collection was moved to the new Carnegie-funded branch – also Staten Island’s first – completed the following year. Tottenville, which had grown immensely over the 19th century due to thriving coastal industries, was the first community city-wide to submit an application for a Carnegie-funded branch when the program was announced in 1901. The resulting one-story, brick structure is Classical Revival in style, with a central, columned entrance portico capped by a triangular pediment, as well as a flared, hipped roof and arched windows. The building’s stucco and wood trim lends a rustic quality that differs from some other Carnegie branches, but was intended to relate to its bucolic context and the village-like character of Tottenville. The Tottenville Branch was designated a New York City Individual Landmark in 1995.