Chelsea, Manhattan

In 1750, British naval officer Thomas Clarke bought a Dutch farm to create his retirement estate, named “Chelsea” after the Royal Hospital Chelsea in London. His property extended from approximately Eighth Avenue to the Hudson—its shore ran roughly along today’s Tenth Avenu —between 20th and 28th Streets. The estate was subdivided in 1813 between two grandsons; Clement Clarke Moore received the southern half below 24th Street while his cousin, Thomas B. Clarke, inherited the northern section.

In the 1830’s, as the street grid ordained by the city in 1811 extended up the island and through his property, Moore began dividing his land into building lots for sale under restrictive covenants which limited construction to single-family residences and institutional buildings such as churches. By the 1860’s, the area was mostly built out with a notable concentration of Greek Revival and Anglo Italianate style row houses, many now preserved within the Chelsea Historic District.

Thomas B. Clarke’s property north of 24th Street was developed around the same time, but with a more varied mixture of row houses, tenements, and industry. By the late 19th century, the area had an unsavory reputation. During the urban renewal era of the mid-20th century, much of it was officially declared a slum and rebuilt with tower-in the- park housing, although clusters of row houses and several significant institutional buildings remain.

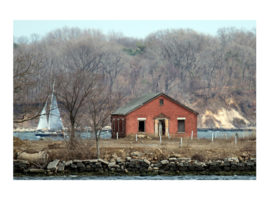

By the 1850’s, infill of the Hudson pushed the waterfront to Eleventh Avenue and within decades to its current location west of Twelfth Avenue. Industry was bolstered by the mid-19-century with the opening of the Hudson River Railroad, and soon the neighborhood supported a range of smaller manufacturers interspersed with sizable operations including iron works and lumberyards. Storage and warehousing became important uses around the turn of the century with the creation of the Gansevoort and Chelsea Piers. By 1920, most of the area’s factories had been replaced by modern facilities. The heart of this industrial district is preserved within the West Chelsea Historic District. Clement Clarke Moore’s rowhouse blocks to the east were largely converted to apartments for a working class employed by these businesses. As they became inactive, an influx of gay residents opened a new chapter of Chelsea history. The neighborhood remains proudly gay friendly today.

The current character of the western part of Chelsea is built on adaptive reuse of

industrial relics. Art dealers drawn to the lofty spaces of former warehouses and factories

began arriving in the 1990’s and built the blocks west of Tenth Avenue into the world’s

largest gallery district. After decades of abandonment, the elevated Hudson River

Railroad was transformed into the High Line, a public park and tourist attraction. Its

innovative design and impact on real estate values spurred a boom in new buildings by

celebrated architects along its length.

Although Thomas Clarke’s 1750 Chelsea estate extended only east to Eighth Avenue

and south to 20th Street, the present-day neighborhood encompasses a larger area.

Its eastern edge along Sixth Avenue lies within the Ladies’ Mile Historic District, named

for the elite shopping district, which saw its first department store open in the 1860’s.

Today, Chelsea contains a variety of historic architecture, including some of the city’s

most intact nineteenth-century residential blocks, significant commercial buildings, and

industrial complexes near the Hudson River.