At Sunset Park’s northern border is the beautiful Green-Wood Cemetery. Opened in 1838, it was the city’s first rural cemetery and its first great park (Central and Prospect Parks would not be built until later in the century). People from all over the city travelled to enjoy its lush surroundings, putting this rural neighborhood on the map before any major development took place here. The cemetery extends from 20th Hamilton Parkway to Fourth Avenue, encompassing 478 acres in the heart of Brooklyn. Its rolling hills, specimen trees, ponds and beautiful grave sites continue to draw visitors. The entire site is a National Historic Landmark.

The cemetery is home to the highest topographical point in Brooklyn, roughly 200 feet above sea level. This is a site in the Battle of Brooklyn, which took place on August 27, 1776, America’s first battle after signing the Declaration of Independence. A bronze statue entitled Altar to Liberty: Minerva by Frederick Ruckstull was erected on the site in 1920, in commemoration of the battle. Minerva’s arm is outstretched toward the Statue of Liberty across New York Harbor.

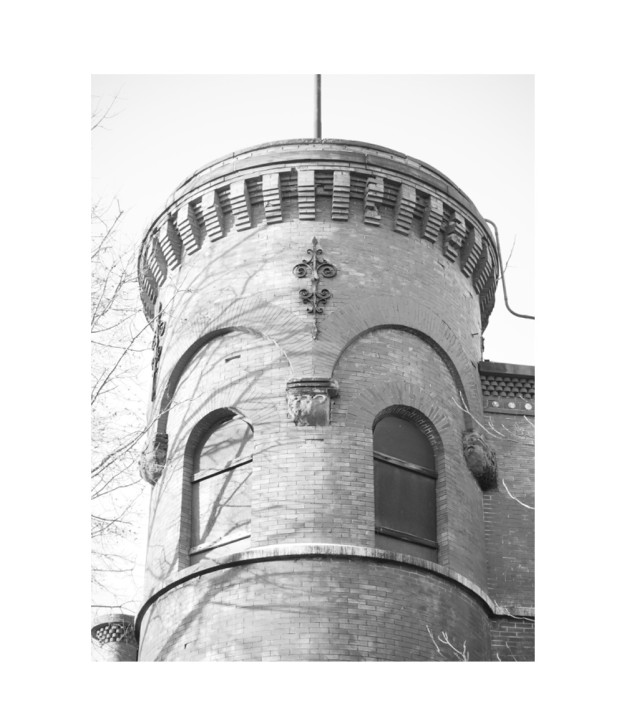

In addition to the cemetery’s lavish mausoleums and memorials, other architectural marvels include the cemetery gates and chapel, which are both designated New York City landmarks. The brownstone gates were designed in the Gothic Revival style in 1861 by Richard Upjohn, the famed church architect who is best known for designing Trinity Church in Lower Manhattan. The chapel was constructed in 1911 after designs by Warren and Wetmore, architects of Grand Central Terminal, and is a reduced replica of Christopher Wren’s Thomas Tower at Christ Church College in Oxford, England.

Among the noted residents of the cemetery are DeWitt Clinton (1769–1828), who, as Governor of New York, was largely responsible for the construction of the Erie Canal; Henry Steinway (1797–1871), founder of Steinway & Sons, piano manufacturers; Samuel F. B. Morse (1791–1872), painter and inventor of the telegraph; William M. “Boss” Tweed (1823–1878), infamous New York politician and leader of Tammany Hall; Nathaniel Currier (1813–1888) and James Merritt Ives (1824–1895), famous printmakers; Susan Smith McKinney-Steward (1846- 1918), the first black female doctor in New York State and third in the country; Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), decorative artist best known for his works in stained glass; Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), artist; and Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990), musician, composer and conductor.