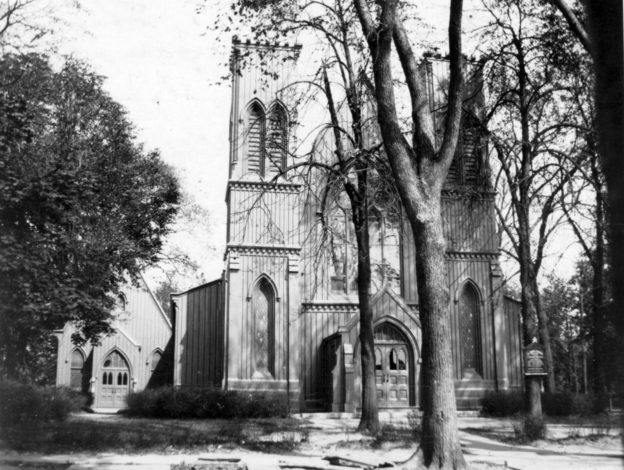

The area of Queens comprising Corona-East Elmhurst was called “Mespat” by the Native Americans and “Middleburgh” by the English colonists. It became part of the Town of Newtown, when it was incorporated in 1683 as one of the three original municipalities (along with Jamaica and Flushing) comprising what is now Queens. It remained largely rural until transportation improvements led to suburban development. In 1854 the Flushing Railroad began service through what is now 44th and 45th Avenues (now part of the Port Washington Branch of the Long Island Rail Road). Anticipating commuter service, a group of real estate speculators formed the West Flushing Land Company and purchased an extensive tract that they subdivided into house lots, naming the new neighborhood West Flushing. Just north (above what is now 37th Avenue) stood the National Race Course, also established in 1854. A massive complex and tourist attraction, it was soon renamed Fashion Race Course and notably hosted the first-ever ticketed baseball game, a best of three series between New York and Brooklyn.

In spite of this enthusiasm, actual building activity remained slow through the 1850s and was curtailed during the Civil War. By 1868, however, Benjamin W. Hitchcock, who also developed much of Woodside, acquired more than a thousand building lots in West Flushing, and most were sold by the early 1870s. Another local developer, Thomas Waite Howard, felt the name West Flushing was too easily confused with Flushing and petitioned the U.S. Postal Service for a more poetic moniker: Corona, the crown (or crown jewel) of Queens. Transit lines continued to expand, including the 1876 introduction of horse car lines to Brooklyn, providing connections to ferries to Manhattan, and trolleys running along Corona Avenue began in the 1890s. In 1898 Queens County was subsumed into Greater New York, and Corona, previously part of Newtown, became its own neighborhood with 2,500 residents. In 1904 the Bankers’ Land and Mortgage Corporation launched a new residential development in north Corona called East Elmhurst, comprising 2,000 building lots along the western edge of Flushing and Bowery Bays. Growth accelerated with the opening of the Queensborough Bridge in 1908 and the East River tunnels to Pennsylvania Station in 1911. Perhaps most significantly, the subway system arrived in 1917 with the opening of the Alburtis Avenue (now 103rd Street-Corona Plaza) station. In the 1930s the neighborhood’s eastern boundary, the dumping ground that was once Flushing Creek, was transformed into “The World of Tomorrow” as the site of the 1939 World’s Fair; it later reprised that role for the 1964 World’s Fair and eventually became Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

From the beginning, Corona-East Elmhurst was a diverse neighborhood. Several of its oldest institutions attest to the 19th century German influence, while many 20th century sites are associated with its Italian-American and Jewish communities. The northern section of this tour boasts a remarkable collection of culturally significant African-American sites. The first recorded residents of African descent arrived in the 17th century and settled along what is now Corona Avenue, a section of which (at 90th Street in Elmhurst) is named for the Rev. James Pennington (1807-1870), an enslaved fugitive from Maryland who became an influential Evangelical Abolitionist on the world stage. In the 1920s, Corona saw an influx of African-Americans, many following the Great Migration from the South, and Afro-Caribbean immigrants from the West Indies. After World War II, the area attracted prominentAfrican-American cultural figures and civil rights activists, many of whom are celebrated on this tour.