750 Amsterdam Avenue

N.Y.C. Board of Education Bureau of Design

1975

The plain style of the Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. School defies the dynamic community activism that facilitated its completion in an era of disinvestment in the city’s black and Latino neighborhoods. However, the school’s almost Brutalist style façades are typical of schools built during the postwar era, with its solid mass of red brick punctuated by narrow bands of windows on the upper stories. In the late 1960s, the city commissioned P.S. 153 to replace the aging and overcrowded P.S. 186, acquiring and clearing a tract of residential buildings. After the school was not included in the Board of Education’s austere annual budget in 1971, the locally-led National Economic Growth and Reconstruction Organization (NEGRO) staged a boycott, with staff and students relocating to temporary classrooms throughout the neighborhood until construction began on P.S. 153. Finally completed in 1975, the school was named after Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., who, in 1941, was the first African-American elected to New York City Council before representing Harlem in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1945 to 1971. In 1994-95, the school constructed an addition on the site of its playground (which was relocated to the roof) to house kindergarten and first grade students.

3560-3568 Broadway

Thomas W. Lamb

1912-13

Although missing its original ornate cornice, the Hamilton Theater, designed by famed movie architect Thomas Lamb, prominently stands out on its corner lot. The building’s round-arch windows feature cast-iron caryatids supporting pediments at the second story and oculi at the third story apex of the arches. The Hamilton is typical of Lamb’s early, smaller neighborhood theaters in its neo-Renaissance style, three-story height and use of terra cotta. As Harlem developed at the end of the 19th century, the theater became one of the many satellite centers of entertainment appearing in the burgeoning residential neighborhoods along the new subway system. The 2,500-seat theater was conceived in 1912 by theater operators B.S. Moss and Solomon Brill to host vaudeville performances, screen motion pictures and feature dining and recreational space in the basement and rooftop. Moss sold his theater empire to Radio- Keith-Orpheum Radio Pictures, Inc. in 1928, which operated the Hamilton until its closure and conversion to a sports arena in 1958.

Riverside Drive between West 138th and 145th Streets

Tippets-Abbett-McCarthy-Stratton / Richard Dattner & Associates

1991/1993

Proposed by the city in 1962, the North River Water Pollution Control Plant was operational by 1986 and began conducting a secondary level of sewage treatment in 1991. One of the country’s most expensive non-military public works projects at the time, the plant removes pollutants for the wastewater of the entirety of Manhattan’s West Side. In 1968, after learning of the plant’s proposed location, West Harlem residents formed two community groups (the West Harlem – North River Environmental Review Board and West Harlem Environmental Action), and became heavily involved in the design process for Riverbank State Park, which was proposed to mitigate the plant’s impact. The partnership between the community, city, state and architecture firm of Richard Dattner & Associates ultimately resulted in a 28- acre park with a skating rink, swimming pool, outdoor amphitheater, restaurant and numerous athletic facilities, which draw millions of visitors each year. Due to the limited load bearing capacity of the plant below, the park’s five buildings are of steel frame construction with metal panels and brick façade tiles.

c. 1891-1905

This row of 15 three-story houses, faced in a variety of masonry materials, follows the topography of West 147th Street as it descends from the heights of Broadway towards Riverside Drive. The houses appear to have been constructed in stages between 1891 and 1909, with the latter date representing the tail end of rowhouse construction in West Harlem, which began with speculative development in the 1880s in response to infrastructure improvements and ended with the spike in property values and subsequent apartment house construction that followed the arrival of the subway in 1904. Despite the consistency in scale, the row features distinct stylistic groupings: 602-610 feature limestone bases with beige brick above; 612-616 contrast with dark red bricks throughout and ornate terra-cotta detailing in the arched doorway surrounds and roofline belt courses; and 618, which covers two lots, is faced entirely in limestone, with a rusticated first floor. Moving west towards Riverside Drive, 620-622 feature ornamented second-story oriel windows topped by balconies, along with elegant bracketed cornices; 624-628 revert back to dark painted brick, with 626 boasting an iron awning over its doorway; and the final group, all faced in limestone, demonstrates a symmetry on the third stories as 632, with three round-arched windows, is flanked by the two rectangular windows and central niche at the tops of 630 and 634.

564 West 150th Street

Berlinger & Moscowitz

1917

Faced in a mix of dark red and clinker brick and topped by a Spanish tile roof, the City Tabernacle of the Seventh Day Adventists’ Church proudly asserts itself on this residential side street. Upon its completion in 1917, the Architectural Review noted that the temple had “an excellent portal and gable arcade,” but noted that “the tiled coping was heavy and superfluous.” The building was originally constructed as the Mount Neboh Temple, which later moved to 130 West 79th Street. Although the façade has lost its Jewish symbols, it retains an elaborate Romanesque arch faced in terra cotta with Egyptian Revival detailing. Rising above the entryway is a series of seven arched windows set within the front gable, which is topped by a dentilled cornice. The church purchased the synagogue in 1945 and eventually took ownership of Mount Neboh’s West 79th Street location, as well, demolishing it in 1984 amid a heated preservation battle.

730 Riverside Drive

George and Edward Blum

1912-13

The 11-story Beaumont Apartments was one of many apartment buildings constructed in West Harlem following the 1904 opening of the subway along Broadway. It is a fine example of George & Edward Blum’s use of the Arts & Crafts style. Rising up from a two-story limestone base, the building’s façade is enlivened by patterned brickwork, geometric tile patterns, ornate iron balconies and terracotta bandcourses. Perhaps in reference to its proximity to the home of John James Audubon, the Blums’ design features decorative terra-cotta medallions with images of owls, eagles and parakeets, among other birds. Similar to many of the luxury courtyard apartment buildings of the time, the Beaumont originally offered apartments ranging from five to eight rooms, including entrance foyers and ample closet space. The building has been the home of such notable residents as Congressman Jacob Javits and writer Ralph Ellison. The Beaumont Apartments is a NYC Individual Landmark.

1828 Amsterdam Avenue

Hugo Kakfa

1885-86

In 1885 Joseph Loth & Company, a silk ribbon manufacturer, commissioned this industrial building, designed in a reversed K plan to ensure well-lit working spaces and constructed of materials that adhered to the city’s strict building codes for mills. While certain components of its design, like the narrow window bays flanked by pilasters, were typical of American mill buildings of the time, the sandstone and red brick façades also had unique ornamentation and panels to identify the firm. The building’s chimney, rising above its three stories, serves as a reminder of the coal-fired boilers that powered the factory’s looms and provided electricity. One of the few industrial enterprises in West Harlem, the mill was built at a time when the neighborhood was characterized by small farms and wood-frame houses. After the company vacated the factory in 1902, the founder’s son Bernard Loth purchased the building and converted it to partial commercial use, constructing a larger entrance on Amsterdam Avenue with cast-iron storefronts. Over the years it also housed offices for a storage company, a movie theater, a dry goods store, a firm producing theater scenery, a recording studio and a basement bowling alley. Today it is home to the New Heights Academy Charter School. The Joseph Loth & Company Silk Ribbon Mill is a NYC Individual Landmark.

1854 Amsterdam Avenue

Nathaniel D. Bush

1871-72

Completed in 1872 as part of a larger effort to improve the city’s police facilities, the 32nd Police Precinct House served as the police department’s outpost in Carmansville, serving a large but sparsely populated area centered around the churches, hotel and residences adjacent to Trinity Cemetery. Officers on patrol could send telegraph messages from signal boxes to the station house, where sleeping quarters provided living space for the captain, sergeants and other officers. Nathaniel Bush, who designed numerous station houses throughout the city during his tenure as the Police Department’s architect, designed the 32nd Police Precinct House in the French Second Empire style. This symmetrical, three-story building is set under a slate mansard roof with a central tower. A two-story jail annex was constructed on West 152nd Street. Situated near the cluster of churches that once formed the core of Carmansville, the Precinct House was purchased by the nearby St. Luke African Methodist Episcopal Church for use as its administration building. The Former 32nd Police Precinct House is an NYC Individual Landmark.

originally Washington Heights Methodist Episcopal Church

1872 Amsterdam Avenue

1869

Built in 1869, this red brick, Gothic Revival style church is one of northern Manhattan’s oldest churches. After an unsuccessful first attempt, a persistent group of five religious leaders established a Methodist congregation in Carmansville in 1867 and constructed their church on land purchased from the Carman estate. Its primary façade consists of two towers flanking a central gable, which contains a stained glass window with ornamental tracery set within a pointed arch. A 1932 newspaper article noted that the church “scarcely has been altered since it was built sixty three years ago,” except for “the remodeling of the main entrance…and the installation of a gallery in the auditorium at the beginning of the century.” The photograph accompanying the article shows a spire on the church’s north tower, which has since been removed. St. Luke’s acquired the church in 1946.

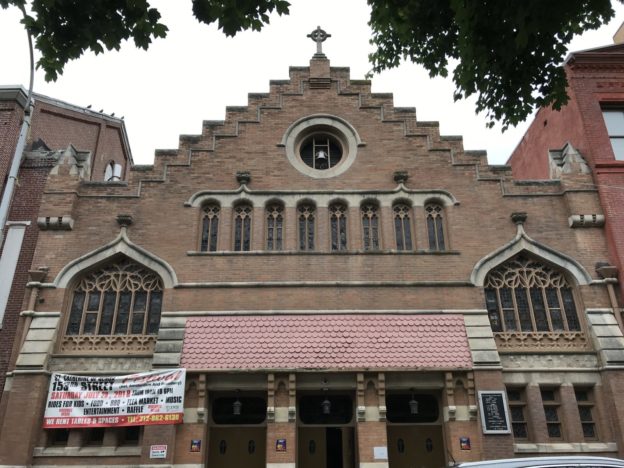

506 West 153rd Street

Thomas H. Poole

1889-90

Founded in 1887 by the Archdiocese of New York, the Parish of Saint Catherine, which originally stretched from West 145th to 161st Streets between Saint Nicholas Place and the Hudson River, held services in a temporary location before constructing this church on West 153rd Street in 1889. Initially serving a population of predominantly first- and second-generation Irish immigrants, the church has evolved with the surrounding community and now holds masses in English, Spanish and Haitian Creole. From 1910 to 2006, the Sisters of Mercy operated a parochial school located within the church until the completion of an annex at 508 West 153rd Street in 1938. The church was designed with elements of both Flemish and Gothic style architecture. The Flemish influence can be seen in the stepped central gable and use of dark red brick, while the two pointed arch windows with elaborate tracery flanking a bracketed entryway are typical of Gothic architecture. Architect Thomas Poole designed a number of eclectic churches, including the Harlem Presbyterian Church in the Mount Morris Park Historic District.

c. 1879-91

John Hemenway Duncan, 1888

West Harlem is graced with several rows of wood-frame houses, a rare sight in Manhattan, where fire codes in the 19th century halted their construction West 153rd Street between Amsterdam Avenue and Broadway contains a number of wood-frame houses, but the stand-outs are nos. 512 and 514, which are vernacular, threestory, three bay houses with covered porches. These houses can be dated by their absence in the 1879 Atlas of the Entire City of New York and their presence in the 1891 Atlas of the City of New York, Manhattan Island, both published by G.W. Bromley. These dates correspond with the 1879 completion of the elevated railway along Eighth Avenue to 155th Street, which spurred the initial wave of speculative development in the neighborhood. A few streets away, nos. 454-460 West 150th Street form a row of four attached wood-frame dwellings, with an asymmetrical roofline of peaked dormers and a central gable over 458-460. Now faced in green and white permastone, historic photographs indicate that these houses once boasted Queen Anne detailing and shingle façades. The group on West 150th Street originally extended to the corner of Convent Avenue and encompassed nos. 450-460, but the end structure was demolished in the early 2000s. They were designed by John Hemenway Duncan, whose notable work includes Grant’s Tomb in Manhattan and the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza.

Vladimir B. Morosov

1966

The otherwise unassuming Russian Holy Fathers Church is smaller than other churches on the block, but makes its mark with a blue onion dome topped by a golden cross. The rise of the Soviet Union and its hostility towards the Russian Orthodox Church prompted North American religious leaders to split from Russian leadership and establish an autonomous jurisdiction. In response, religious leaders loyal to the Patriarchate of Russia founded the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia and established new parishes, of which Holy Fathers Church was the first. Founded in 1928 and originally located on Fifth Avenue between 128th and 129th Streets, the Russian Holy Fathers Church moved to a converted space on West 153rd Street in the late 1930s. By 1966, under the leadership of Protopriest Alexander Krasnoumov, the congregation had raised funds to construct its own building, remaining on West 153rd Street a block from its original location.

550 West 155th Street

church: Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, 1912-15; vicarage: Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson, 1911-14

601 West 153rd Street

James Renwick, Jr., 1843; re-design: Calvert Vaux, 1881

Located at the northern edge of West Harlem, the Church of the Intercession traces its roots to the 1840s, when prominent residents, including Richard Carman and John James Audubon, petitioned a priest based in Harlem to hold Episcopal services in a building in Carmansville. Faced with overcrowding and financial insolvency by the turn of the century, the Church of the Intercession negotiated with Trinity Church to construct a new building on the grounds of its cemetery, thereby losing its independent status and becoming the Chapel of the Intercession until again becoming its own parish in 1976. The Late English Gothic Revival church and its Tudor Revival vicarage are constructed of ashlar with limestone trim. Founded in 1842, Trinity Cemetery was established to provide burial grounds outside of Trinity Church’s congested environs downtown. The cemetery’s hilly terrain, now bisected by Broadway, serves as the final resting place of, among others, John Jacob Astor Sr., John James Audubon and Clement Clarke Moore, author of “Twas the Night Before Christmas.”

Although European settlers had begun farming the area now known as West Harlem in 1625, the community was not formally incorporated as the village of New Harlem (or “Nieuw Haarlem” in Dutch) until 1658. By the time Richard Carman began purchasing farmland in the area surrounding West 152nd Street in the 1830s, roads had been extended into the neighborhood and country estates were established as summer retreats for the city’s elite. In the 1840s, development started to encroach on this pastoral landscape as the Croton Water Aqueduct stretched through the neighborhood on its way downtown, and Trinity Church acquired a large parcel of land to construct a cemetery. After the Hudson River Railroad established a stop at the foot of West 152nd Street in 1842, the thoroughfare became the nucleus of the newly named village of Carmansville.

Carmansville featured multiple residences, several churches, a hotel and a new headquarters for the city’s 32nd Police Precinct, which was linked by telegraph to the rest of the city. The construction of an elevated railway along Eighth Avenue in 1879 further tied Carmansville to the burgeoning metropolis to the south. While the elevated railways facilitated the speculative development of blocks of brownstones for the middle class in central Harlem, the heights farther west, then called “lower Washington Heights,” saw more gradual development. When the Joseph Loth & Company Silk Ribbon Factory, one of the few industrial enterprises in the community, opened its doors at Amsterdam Avenue and West 150th Street in 1886, its immediate environs consisted of truck farms and clusters of houses.

By the time the Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) Company inaugurated subway service along Broadway with a terminus at West 145th Street in 1904, this scene had changed dramatically to one of elegant rowhouses constructed in styles ranging from the Queen Anne to the Dutch Revival, lining the streets between Amsterdam and Broadway. Marking the urbanization of the area, one of the last undeveloped portions of Manhattan’s street grid disappeared when the stretch of West 150th Street west of Broadway was finally ceded to the city and opened as a public thoroughfare in 1906. Residential development was accompanied by improvements associated with an established urban neighborhood, including the opening of the Hamilton Grange Branch Library in 1906, the extension of Riverside Drive into Audubon Park in 1911 and the completion of the Church of the Intercession in 1915. While the turn of the century brought an influx of African-Americans into central Harlem, transforming that neighborhood into a national center of black culture, West Harlem’s black population gradually increased into the 1920s and 1930s.

In the post-World War II era, West Harlem’s buildings were plagued by poor maintenance and abandonment as middle-class residents moved to the suburbs and those who remained faced poverty and institutional neglect. Despite these challenges, West Harlem residents took steps to strengthen their community’s identity and affirm its resiliency. In the 1970s, residents organized to advocate for the construction of Riverbank State Park atop the maligned North River Water Control Plant, while Arthur Mitchell located his newly established Dance Theatre of Harlem in a renovated garage at 466 West 152nd Street. Today, local organizations continue to fight to preserve West Harlem and promote its unique identity as increased development threatens this dynamic community and its architectural beauty.