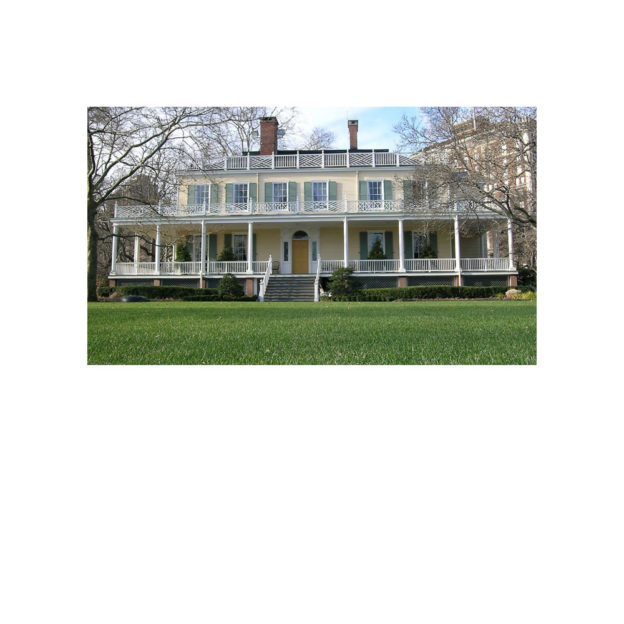

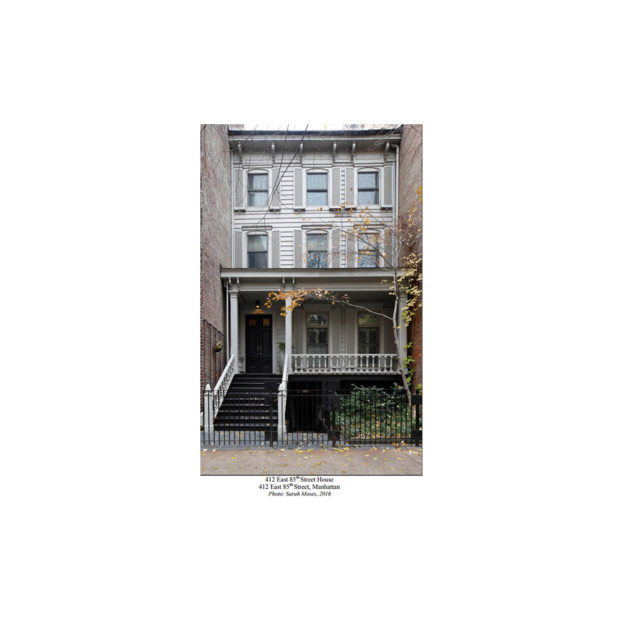

The recorded history of Yorkville begins in the 17th century when it was a tiny hamlet on the Boston Post Road, which ran northward from New York at the tip of Manhattan. It was long the province of farmers and wealthy landowners, including merchant Archibald Gracie, whose riverfront estate is now the official residence of New York’s mayor. In the 19th century, the area slowly began its transformation into the urban neighborhood we see today. Like most such transformations in New York, these changes were largely propelled by transportation improvements. In 1834, the New York & Harlem Railroad (later the New York Central) opened a station at 86th Street and Park Avenue, and in the 1850s, horsecar lines were completed along Second and Third Avenues. This opened the neighborhood to low-density residential development, and a few remnants from this era remain, including the wood-framed house at 412 East 85th Street.

After two major economic depressions (in 1857 and 1873) and the Civil War, the area was finally primed for a major wave of construction in the late 1870s with the arrival of mass transit. The Third Avenue elevated train was completed in 1877-78, and the Second Avenue elevated in 1879-80. In a relatively short period, the Upper East Side was entirely built up, and the elevated trains segregated the area along ethnic and economic lines. West of Third Avenue, wealthy homeowners established the city’s most exclusive neighborhood, while east of Third Avenue became known as Yorkville, a thriving immigrant community, which in many ways was a second-generation immigrant neighborhood—the place that recent arrivals aspired to live after filtering through the older, more congested downtown districts like the Lower East Side. Its housing stock was largely composed of tenements, but they were brand new and built after the Tenement Law of 1879 (the “Old Law”), so were subject to improvements. There were abundant employment opportunities, notably in the neighborhood’s breweries and at the Steinway piano factory in Queens, which was a short ferry ride away from the foot of East 92nd Street.

The largest and perhaps most visible immigrant group in Yorkville was the Germans. Already an established presence in New York following a wave of immigration in the 1840s, they began moving uptown from their Lower East Side settlement, Kleindeutschland (Little Germany), by the early 1880s. They brought with them many of their institutions, including churches and benevolent organizations, as well as cultural and commercial enterprises, such as beer halls and music societies. East 86th Street became the community’s main artery. Other groups had micro-neighborhoods in Yorkville, as well. Czechs began moving to the area in the 1880s and settled mostly between 71st and 75th Streets. Hungarians arrived around the turn of the century on East 79th Street, though their institutions can be found throughout the neighborhood.

Yorkville’s heyday as a distinct immigrant community was relatively short-lived. German immigration to New York peaked in 1882, and by the early 20th century, Yorkville’s Germans were already moving farther afield, using the recently built subway to access newer, more affordable neighborhoods in the outer boroughs. At the same time, anti-German sentiment during World War I led many Germans to downplay overt displays of national heritage. The Second Avenue and Third Avenue elevated trains were demolished in the 1940s and 1950s, respectively, removing one of the major boundaries between Yorkville and the rest of the Upper East Side. The neighborhood has seen its share of redevelopment since then, with large apartment buildings towering over the tenements. The recent opening of the Second Avenue subway re-established one of the area’s transit links, but may also put additional pressure on Yorkville’s surviving historic resources.