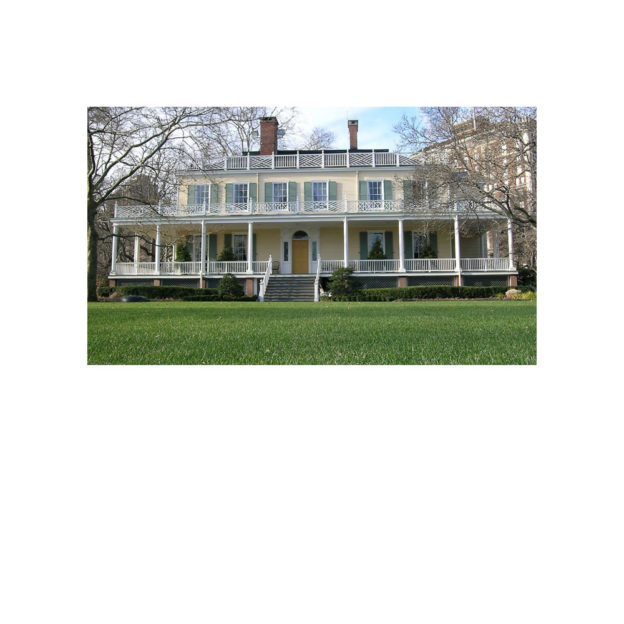

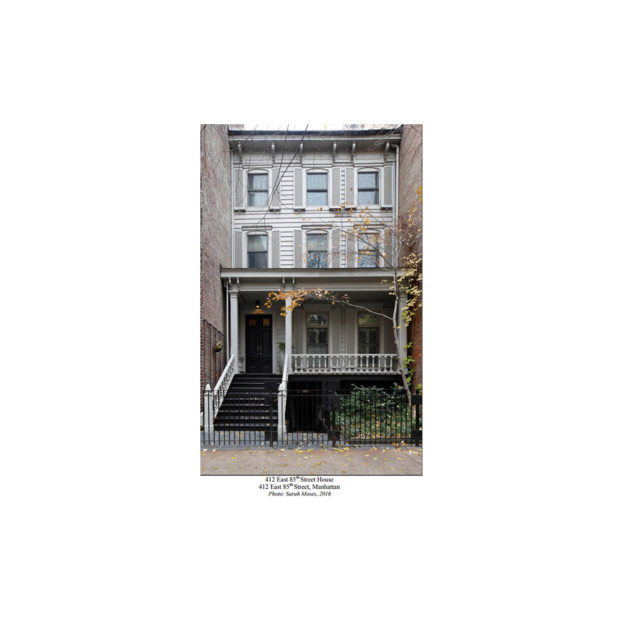

La historia de Yorkville comienza en el siglo XVII, cuando aún era una pequeña aldea en el Boston Post Road, el cual se extendía hacia el norte desde Nueva York, que en ese momento solo ocupaba la punta de Manhattan. Por mucho tiempo fue la provincia de granjeros y hacendados acaudalados, incluyendo al comerciante Archibald Gracie, cuya hacienda a la orilla del río es actualmente la residencia oficial del alcalde de Nueva York. En el siglo XIX, el área comenzó a transformarse en el barrio urbano que conocemos hoy. Como muchas transformaciones de este tipo en Nueva York, el cambio fue impulsado por las mejoras en el sistema de transporte. En 1834, el Ferrocarril de Nueva York y Harlem (posteriormente conocido como el New York Central) abrió una estación en 86th Street y Park Avenue, y en la década de 1850, una línea de tranvía impulsado por caballos fue finalizada a lo largo de Second Avenue y Third Avenue. Esto dio como resultado construcciones residenciales de baja densidad, algunos remanentes de estas construcciones aún existen, incluyendo 412 East 85th Street.

Después de dos grandes crisis económicas (en 1857 y 1873) y la Guerra Civil, el área estaba preparada para una gran ola de construcción a finales de la década de 1870 con la llegada del transporte en masa. El tren elevado de Third Avenue fue finalizado en 1877-78 y el de Second Avenue en 1879-80. En un período de tiempo relativamente corto, el Upper East Side fue completamente urbanizado, y el área fue segregada con trenes hechos para razas y clases económicas específicas. Al oeste de Third Avenue, los propietarios acaudalados establecieron el barrio más exclusivo de la ciudad, mientras que al este de Third Avenue vivía una próspera comunidad de inmigrantes, la cual ya era conocida como Yorkville en la década de 1860 y estaba compuesta en su mayoría por inmigrantes de segunda generación. Yorkville se convirtió en un barrio en el cual los inmigrantes recién llegados aspiraban a vivir después de haber pasado por distritos más congestionados del centro de la ciudad, como el Lower East Side. El conjunto de viviendas en el área estaba compuesto en su mayoría por inquilinatos, pero recién construidos y erigidos después de la Ley de Inquilinatos de 1879 (la “Old Law”), por lo cual estaban sujetos a mejoramientos. En ese tiempo, había abundantes oportunidades de empleo, especialmente en las cervecerías del barrio y en la fábrica de pianos Steinway en Queens, la cual estaba a una corta distancia en ferry desde East 92nd Street.

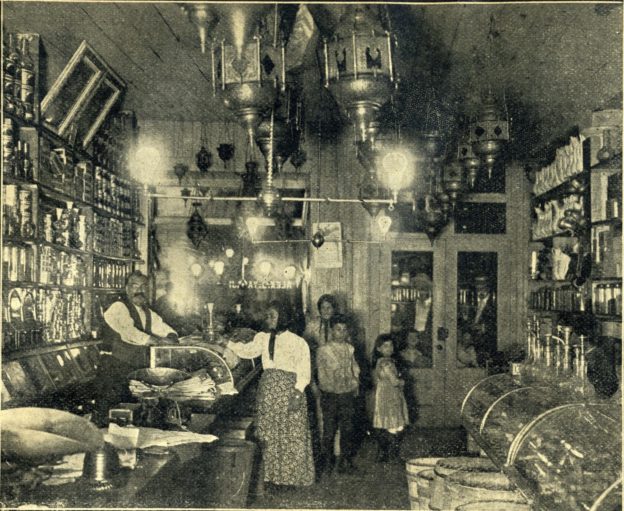

El más grande y visible grupo de inmigrantes en Yorkville eran los alemanes. Con una presencia ya establecida en Nueva York después de la ola de inmigración de la década de 1840, las comunidades alemanas empezaron a mudarse hacia el norte de la ciudad, dejando su asentamiento en el Lower East Side, conocido como Kleindeutchland (Pequeña Alemania). Al finalizar el siglo, Yorkville se había convertido en el principal barrio alemán de Nueva York. Los alemanes trajeron consigo sus instituciones, incluyendo iglesias y organizaciones de benevolencia, así como también emprendimientos culturales y comerciales, como cervecerías y sociedades musicales. East 86th Street se convirtió en la arteria principal de la comunidad alemana. Otros grupos también tenían micro barrios en Yorkville. Los checos empezaron a mudarse al área en la década de 1880 y se asentaron principalmente entre 71st Street y 79th Street. Los húngaros llegaron a inicios de siglo XX a East 79th Street, aunque sus instituciones se pueden encontrar en todo el barrio.

El apogeo de Yorkville como una comunidad de inmigrantes fue relativamente corto. La inmigración alemana a Nueva York alcanzó su pico en 1882 y, a comienzos del siglo XX, los alemanes en Yorkville ya habían empezado a mudarse a otros barrios más nuevos y asequibles, usando los subterráneos recientemente construidos. Al mismo tiempo, el sentimiento en contra de los alemanes estaba creciendo durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, lo cual llevó a muchos alemanes a minimizar sus sentimientos de herencia nacional. Los trenes elevados de Second Avenue y Third Avenue fueron demolidos en las décadas de 1940 y 1950 respectivamente, eliminando una de las mayores divisiones entre Yorkville y el resto del Upper East Side. El barrio ha experimentado una reurbanización desde entonces, con construcciones de apartamentos que sobrepasan a los inquilinatos. La apertura reciente del subterráneo de Second Avenue restableció una de las conexiones de tránsito del área, pero también puede ejercer presión para preservar los recursos históricos que quedan en Yorkville.