22 Barclay Street

1836-40

John R. Haggerty and Thomas Thomas

Saint Peter’s Roman Catholic Church is one of the finest examples of Greek Revival architecture anywhere in the city, featuring hallmarks of the style in its monumental hexastyle Ionic portico, massive pediment and austere, smooth granite facades with crisp punched window openings. St. Peter’s has the distinction of being New York State’s first Catholic parish. Over the centuries, many notable New Yorkers worshipped here, such as Pierre Touissaint and Mother Seton, who professed her faith here. This church was also the root of the Knights of Columbus in New York State. The first house of worship was built on this site in 1786 and demolished in 1836, to make way for the present church, designed by architects John R. Haggerty and Thomas Thomas. St. Peter’s fostered the city’s first Syrian-American parish, St. George’s, offering them space in which to worship before the congregation had the means to purchase or build their own building. Saint Peter’s Roman Catholic Church is a NYC Individual Landmark and listed on the State and National Register of Historic Places.

90 West Street

1905-07

Cass Gilbert

Designed by Cass Gilbert, architect of the Woolworth Building and one of New York City’s preeminent commercial and industrial designers of the early 20th century, the West Street Building exhibits the hallmarks of the early Manhattan skyscraper in its classical detailing and column-like “base-shaft-capital” facade composition. Constructed in 1905-07, the building’s location on what was then the industrial waterfront, was key to the shipping and railroad concerns it served. It was damaged during the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, but spared the fate of nearby St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church, which was buried and damaged beyond repair. The former 1830’s row house turned church at 155 Cedar Street was completely destroyed when the South Tower fell. The West Street Building is a NYC Individual Landmark and listed on the State and National Register of Historic Places.

105-107 Washington Street

1925

John F. Jackson

The Downtown Community House was built in 1925-26 through a charitable donation given by financier William Hamlin Childs to the Bowling Green Neighborhood Association, a settlement house founded in 1915 to serve residents of Lower Manhattan. The Downtown Community House was intended to expand social services to a large multi- ethnic immigrant resident community. The Colonial Revival style brick building housed a worship space, nursery, recreation facilities, clinic and residences. In a 1925 article about the building’s cornerstone- laying ceremony, The New York Times noted that ‘’Wall Street financiers rubbed elbows with Nordic, Slav and Levantine neighbors in colorful crowds which packed Washington Street.’’ By the 1940s, the Downtown Community House was being used for storage and offices, presumably because of the mass displacement of its patrons due to the construction of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. By the late 1960s, the building was in use as a union hall. The Buddha reliefs within the second-floor window tympana date to the building’s later incarnation as a Buddhist temple.

103 Washington Street

Current facade 1929-30

Harvey F. Cassab

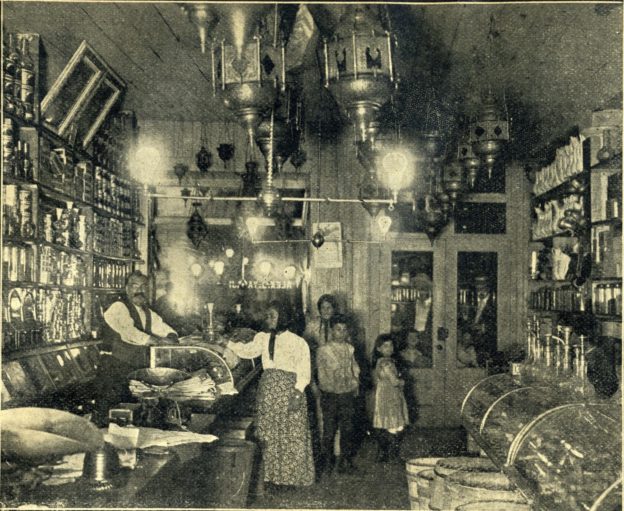

This former row house turned church embodies the community of immigrants that gave rise to Manhattan’s “Syrian Quarter” in the last two decades of the 19th century and into the early 20th, many of whom were Melkite Greek Catholics from the former Ottoman province of Syria (which included present-day Syria and Lebanon). The parish of St. George was formed in 1889 as America’s first Melkite congregation (Christians who recognized the Pope in Rome but maintained the Byzantine Rite). One of the first services was held in the basement of St. Peter’s Church on Barclay and Church streets, and in 1925 the congregation moved into the former row house at 103 Washington Street (which had been raised from three stories to five when it became a boarding house in 1869). Lebanese-American architect Harvey Cassab designed the striking white terra cotta neo-Gothic style façade completed in 1929. At its height the Syrian Quarter was home to numerous churches, factories,and small businesses that were part of an international network of trade, and several Arabic language newspapers. Landmarked in 2009, St. George’s remains an eloquent reminder of a time when Washington Street was the “Main Street” of Syrian America. St. George’s Syrian Melkite Church is a is a NYC Individual Landmark.

Photo by Carl Forster, NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission.

67 Greenwich Street

1809-10

The Robert and Anne Dickey House was built in 1809-1810, making it one of only a handful of houses surviving from this period in Manhattan. The four-bay front facade features Flemish bond brickwork, flat and splayed keystone lintels, and a later door hood installed as part of an 1872 renovation by architect Detlef Lienau, when the building was in use as a tenement. The rear of the house retains the most striking feature of its Federal- period construction, which is the rounded bay facing Trinity Place. The Dickey House will serve as the entrance to the new school in the base of a tower rising directly next to and behind it. The Dickey Home is a NYC Individual Landmark.

Photo courtesy of The Library of Congress.

94 Greenwich Street

ca. 1799-1800

The three-and-a-half story brick house standing at the northwest corner of Rector and Greenwich Streets is among the remarkable group of Federal-era houses still surviving below Chambers Street, the oldest section of the city. 94 Greenwich Street still retains its Flemish-bond brickwork, splayed brick or marble lintels (on the Greenwich and Rector Street facades, respectively), and the top section of its original peaked roof, visible along Rector Street. Other survivors of this early period include the Watson House at 7 State Street and the Dickey House at 67 Greenwich Street. At

the southeast corner of the intersection is George’s restaurant, established in 1950 and apparently the last of the area’s Middle Eastern businesses. George’s suffered significant structural damage in the events of September 11, and owner George Koulmentas, with his son Billy, chose to rebuild in place as a low-scale restaurant. 94 Greenwich Street is a NYC Individual Landmark.

Photo by Christopher D. Brazee, NY Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Edgar Street, Greenwich Street, Trinity Place

2019

NYC Dept. of Parks and Recreation, Sara Ouhaddou, artist

For several years local advocates have been pushing the city to embrace their plan of combining the two small pocket parks located at the juncture of Greenwich Street, Edgar Street (reputedly the shortest street in Manhattan), Trinity Place and the Brooklyn- Battery Tunnel exit into one larger, continuous park. Their efforts are bearing fruit: the City is set to begin construction on what will be known as Elizabeth H. Berger Plaza, in honor of the late head of the Downtown Alliance. The plaza’s design will reroute the tunnel exit and merge the largely hardscaped parks into a unified landscape featuring more greenery with public art by Franco-Moroccan artist Sara Ouhaddou. Through the efforts of the Washington Street Historical Society, the plaza will also honor the local Syrian and Lebanese-American heritage by incorporating interpretive displays on Little Syria and its notable Arab-Americans residents, like writer and artist Kahlil Gibran.

Cunard Building

1917-21

Benjamin Wistar Morris with Carrere & Hastings

The intersection of Morris and Greenwich Streets perhaps best embodies the economic and technological forces that reshaped Little Syria, and Lower Manhattan in general, over the course of the 20th century. On the southeast corner stands the rear facade of the massive Cunard Building, one of the first major skyscrapers to be built under the 1916 zoning resolution, which established

certain limits on building bulk and massing in order to avoid the complete “canyonization” of Lower Manhattan. Across the street from the Cunard Building lies the giant trench that is the exit to the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, a monument to mid-century automobile-based urban planning. It is here that Greenwich Street forks off into Trinity Place, notable as the location where one of Manhattan’s earliest elevated rail lines split into two lines running northwards along Sixth and Ninth Avenues, respectively. A historic mast-arm lamppost remains at the north side of Morris Street, in the section of median that will shortly become the southern part of an expanded, redesigned Elizabeth Berger Plaza. Famed photographer Berenice Abbott photographed Morris Street at Greenwich Street in the 1930s, capturing the last remaining tenement building juxtaposed with the towering Cunard Building. The Cunard Building is a NYC Individual Landmark and listed on the State and National Register of Historic Places.

Photo courtesy of The New York Public Library.

Battery Place, Greenwich Street to Washington Street

1940-50

Ole Singstad, chief engineer through 1946; Ralph Smille, chief engineer after 1946; Erling Owre, architect

The Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, which connects Lower Manhattan with Brooklyn, was constructed over a ten-year period from 1940 to 1950—including a three-year wartime hiatus—and is the longest tunnel of its type in North America. It replaced the low-rise buildings of the former Syrian Quarter. The severe-looking Moderne style ventilation building at Battery Place was designed by Parks Department architect Aymar Embury II and completed in 1950. The facade inscription facing Battery Park commemorates the 1946 consolidation of the city’s Tunnel Authority and Triborough Bridge Authority into the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority. The other architecturally notable vent building is the white octagon located off the northern tip of Governors Island, designed by the successor firm to McKim, Mead, & White. The Tunnel was renamed in 2012 in honor of former New York State Governor Hugh L. Carey. Historic photo courtesy of The Library of Congress.

Castle Clinton: 1808-11, Lt. Col. Jonathan Williams and John McComb, Jr.

Originally sited on an island some 300 feet off the Battery, Castle Clinton was built for the War of 1812 as one of a pair of fortifications, the other being the still-surviving Castle Williams on the northern shore of Governors Island. The horseshoe-shaped brownstone monument has seen many and varied incarnations during its over 200-year history, including pleasure garden and concert hall, aquarium, ruin and finally National Monument. It also served as an immigration station, processing nearly eight million immigrants newly arrived in America — as compared to the roughly 12 million immigrants who passed through Ellis Island, its successor.

During the 1930s and 40s Castle Clinton was at the center of an epic preservation battle between legendary city Parks Commissioner Robert Moses and opponents of his plan to raze the structure for a parkway and bridge connecting Manhattan’s Battery with Brooklyn. A coalition of historic, art and landscape societies, led by the Regional Plan Association’s Robert McAneny, advocate Albert S. Bard, Manhattan Borough President Stanley Isaacs, and admiralty attorney C. C. Burlingham organized as the Central Committee of Organizations Opposing the Battery Bridge to fight Moses’ plan. Moses lost, Castle Clinton was declared a National Monument in 1946 and the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel was built instead. Castle Clinton is a NYC Individual Landmark and listed on the State and National Register of Historic Places.

7 State Street

1793

attributed to John McComb, Jr.; extension 1806

Originally constructed in 1793 as the elegant private residence of James Watson, a merchant and the first Speaker of the New York State Assembly, the Federal style mansion at 7 State Street is a remarkable survivor from the early period when Lower Manhattan was home to the city’s wealthy and fashionable families. It is also notable for its long association with the history of Roman Catholicism in America.

Elizabeth Ann Bayley (1774-1821), a Staten Island native and religious pioneer who later became the sainted Mother Seton, briefly lived at 8 State Street before an 1803 trip to Italy that resulted in her conversion to Roman Catholicism (in an 1805 ceremony that took place nearby at St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church on the corner of Church and Barclay streets). In 1884, 7 State Street became home to the Parish of Our Lady of the Rosary to better serve the Irish immigrants. In 1965, it was restored and protected with landmark status and, in the same year, the Classical-Revival style Our Lady of the Rosary church containing a shrine honoring Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton was constructed immediately to the left. The first American citizen to reach official sainthood, Mother Seton was canonized in 1974, on the 200th anniversary of her birth.

To the east of the building was the Leo House, a settlement house founded by the German Catholic Church in 1889 to serve German immigrants. The settlement house moved in 1926 to West 23rd Street in Chelsea. To the right of Mother Seton Shrine sits a skyscraper at 1 State Street Plaza, a building which began the wave of displacement faced by the immigrant community of the area by replacing the tenements and rowhouses that formerly occupied its space. Mother Seton Shrine is a NYC Individual Landmark and listed on the State and National Register of Historic Places.

2011

NYC DOT; AECOM, construction manager; Michael Victor Ruggiero, Landscape Architect; Ben van Berkel, UNStudio, Sculptor

Situated at the foot of Manhattan within view of New York Harbor, this plaza memorializes the early contact between the Native American inhabitants of Manhattan and its European explorers. Its centerpiece, the Plein and pin-wheel-shaped Pavillion, was donated by the Kingdom of the Netherlands to commemorate Henry Hudson’s arrival in 1609. The plaza’s namesake, Peter Minuit, was the third Director of the Dutch New Netherland colony, who in 1626 entered into an agreement with the indigenous Lenape. Though widely considered an outright purchase by subsequent colonists, this agreement was closer to a shared use contract allowing both parties equal access to live on and harvest the bounty of lower Manhattan. By the 1660s, the settlement of New Amsterdam was a thriving and diverse trading port with 18 languages spoken in the neighborhood. A bronze replica of the 1660 plan is on the north side of the plaza at State Street. Today, this plaza and transit facility is the city’s “busiest intermodal hub,” serving commuters by foot, bike, ferry, subway, and bus.

Photo by Wally Gobetz.