municipal cemetery in the United States. It was part of the property purchased by the English physician Thomas Pell from Native Americans in 1654. On May 16, 1868, the Department of Charities and Correction (later the Department of Correction or “DOC,” which split off from the Department of Public Charities in 1895), purchased Hart Island from the family of Edward Hunter to become a new municipal burial facility called City Cemetery. Public burials began in April 1869. Since then, well over a million people have been buried in communal graves with weekly interments still managed by the DOC. The burials expanded across the entire island starting in 1985. Over its 150-year municipal history, it has also been home to a number of health and penal institutions. The island is historically significant as a cultural site tied to a Civil War-era burial system still in use today.

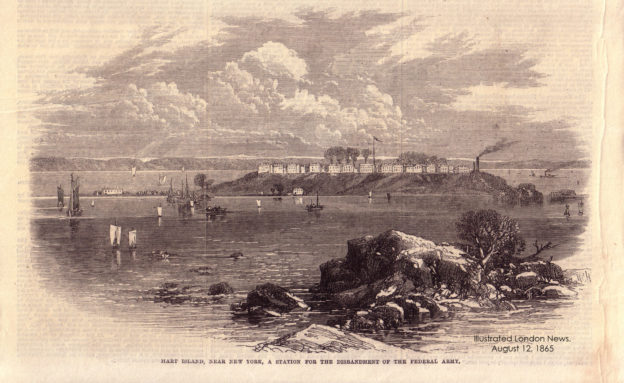

During the Civil War, in April 1864, the federal government leased Hart Island as a training camp for the 31st regiment of the United States Colored Troops. For four months in 1865, Hart Island was host to a prisoner-of-war camp for 3,413 captured Confederate soldiers. Hart Island was also leased to the federal government for training and defense purposes during World War II and the Cold War. Following the Civil War, personnel from the U.S. Sanitary Commission were stationed at Bellevue Hospital and helped to establish a morgue for examining and identifying the dead. In 1866, the City Council passed new sanitary codes prohibiting new burial grounds from opening in New York City. The Potter’s Field then in use on Wards Island (established in the 1840s) closed, and City Cemetery on Hart Island (then part of Westchester County) opened in 1869.

In 1872, a highly efficient grid system of burials began on Hart Island that is largely unchanged today. Trenches were laid out in three layers of 50 graves. In 1931, this system changed to sections of two across and three deep with 50 bodies per section. Each pine box is listed as a grave and recorded in ledger books. Consequently, the City’s mortuary service, still operated by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner at Bellevue Hospital, can readily disinter a body for further examination or return it to families claiming the deceased at a later date. In 1931, the City also began recycling graves, which is legal after a body has decomposed to skeletal remains. Due to these practices, City Cemetery is large enough to accommodate New York City’s burial needs indefinitely, making it an important municipal resource.

In 2013, the New York City Council passed legislation requiring the DOC to post its database of burials online and to list its visitation policy. In 2013, a group of eight women working with a charity, The Hart Island Project (HIP), petitioned the City to visit the graves of their infants buried on Hart Island. In 2015, the New York Civil Liberties Union filed a class action lawsuit establishing rights for families to visit graves on Hart Island. Families are now able to visit once a month by appointment. HIP was founded in 1991 to provide public access to information about burials and, in 2014, launched The Traveling Cloud Museum, an online database with an interactive map for locating burial sites and collecting stories of the recently buried. These resources are intended to reconnect Hart Island with communities across the globe.