Crown Heights South, Brooklyn

Located along the hilly terminal moraine between the prosperous communities of Bedford and Flatbush, Crown Heights South was considered a rocky no-man’s land of scrub farmland for most of the 19th century. During that time, it was home to subsistence farmers whose homes dotted the landscape, as well as poor Irish and black families who settled in shantytowns called “Crow Hill” and “Pigtown” by a derisive press. In 1846, this was where the city of Brooklyn placed the Kings County Penitentiary, as far from downtown Brooklyn as was feasible.

By 1874, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux had completed Eastern Parkway as a Parisian-style boulevard to extend the picturesque character of Prospect Park into the expanding residential neighborhoods of Brooklyn. The parkway, which followed the moraine through the neighborhood that was now called Crown Heights, was designed to be lined with fine homes and mansions, though this housing never developed as Olmsted and Vaux envisioned. The thoroughfare did bring attention to the neighborhood, though, and formed the border between Crown Heights North and Crown Heights South in later years. While the northern side of Crown Heights was fully built up by 1900, it wasn’t until after the new century began that large-scale residential development began in southern Crown Heights. The north-south corridors of Nostrand, Bedford, Rogers and Franklin Avenues were already important transportation corridors, leading to the paving of Union, President, Carroll and other cross streets.

Several major changes led to the development of Crown Heights South after the turn of the 20th century. These included the 1907 demolition of the infamous Kings County Penitentiary, which was replaced by a Jesuit Prep school and college; the 1913 construction of Ebbets Field, home to the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team; the development of Brooklyn’s famous Automobile Row, with its showrooms and service centers, which flourished on Bedford Avenue between 1905 and 1945; and the presence of the nearby Brooklyn Museum, which opened in 1897. Encouraged by these developments, as well as the new subways constructed under Eastern Parkway, developers built up entire blocks at a time with new housing. With the exception of certain blocks of single-family mansions, much of what was built was designed for multiple families, as the age of the single-family rowhouse had nearly passed. Crown Heights South displays a fine array of architectural styles of the early 20th century, designed by such prominent Brooklyn architects as Montrose W. Morris, Axel Hedman, J. L. Brush, Arthur Koch and Slee & Bryson in the Revival styles popular at the time: Renaissance, Colonial, Flemish, Tudor and more.

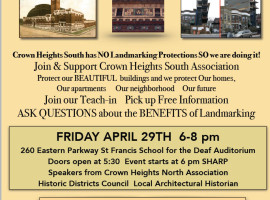

Today, the neighborhood retains its vibrant mix of residential architecture, including attached rowhouses, detached mansions and grand apartment buildings, as well as some fine religious buildings and grand institutions. One of its most well-known structures is the Bedford Armory , the city’s first mounted cavalry-unit armory that occupies an entire city block. The armory’s future is a source of controversy, with developers seeking to construct housing on the site and community members vying to preserve the building. Unfortunately, none of Crown Heights South’s architectural gems have been designated as landmarks by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Local advocates, including the Crown Heights South Association, formed in 2016, are working to survey and advocate for the neighborhood to ensure that any future changes are sensitive to its rich past.